The Public Burning Book Review

Richard Nixon isn’t as bad as you think he is, pleads his Presidential Library’s Twitter account. Firing an FBI director is not Nixonian. Welcome to Trumpland, where one of the worst Presidents in history doesn’t want to be associated with the chaos that sits in the chair. For those like me, who follow the news closer than ever these days, reality feels like a heavy-handed morality lesson in an overly-caricatured cartoon. There are even Twitter accounts dedicated to calling out the bad scriptwriting that the Trump White House has handed us.

Robert Coover’s The Public Burning is a searing satire about a kind of political witch hunt. No, it did not involve the President, but two Jewish-Americans blamed for passing atomic secrets onto the Soviet Union. Historically, Julius Rosenberg certainly did pass classified information onto the Soviets and his wife aided and abetted in note-taking and recruiting other people for their cause. The issue then, in both the novel and history, was whether they deserved the death penalty. The book takes place from June 17th to sundown of Friday June 19th in which lawyers and judges are frantically pouring over last-minute stays, and the American people, led by Uncle Sam himself—a capricious Greek-god like figure with a taste for sodomy—are building a public execution stage in Times Square.

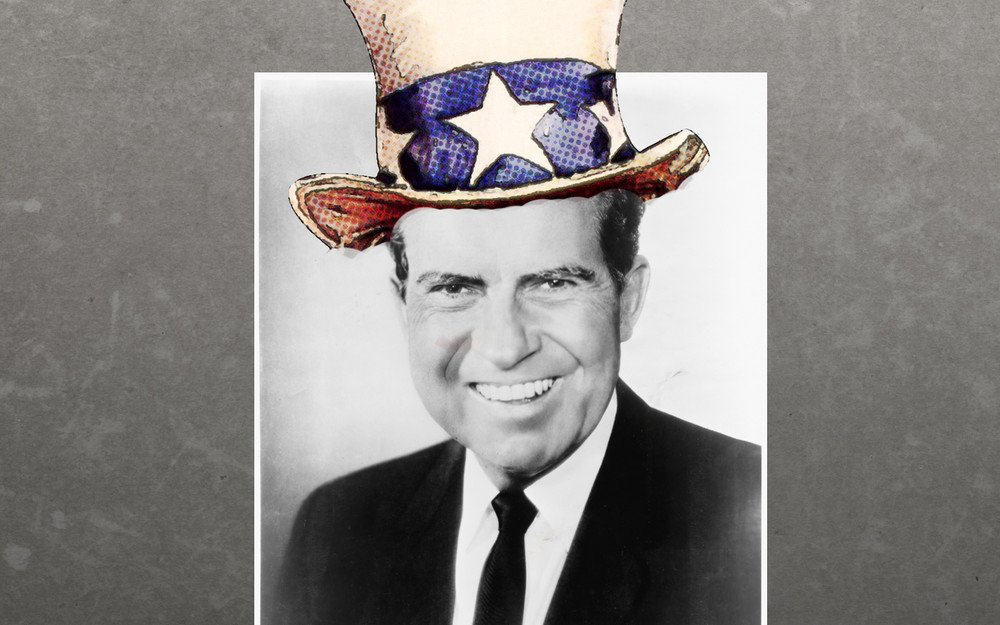

Our guide and chief narrator is Vice President Richard Nixon. Coover’s Nixon is an Augustinian confessor; confession being an act of performance, of notoriety, of justification and self-defense. Nixon craves the power of the Presidency, to have Uncle Sam possess his body and take control of the nation. He is vain, ruminating and delusional. His every interaction is marred by gaffes and nervous tics—day-dreaming while in the Senate, misunderstanding a cabbie, falling pants down on the Times Square execution stage. Any perception below the surface reveals that he is so obviously a fraud. His deepest held beliefs, mired in political cynicism, could be passed around as a Trumpian quote, “You’ve got to win, or the rest doesn’t matter. I believe in fighting it out, in hitting back, giving as good as you get, you’ve got to be a politician before you can be a statesman…” And while the two may sound like each other and each has had suspicious campaign practices, Coover manages to deliver a kind of sympathy for Nixon. In a pre-Internet age Coover must have exhausted himself building the exact biography he needed for Nixon. Most interestingly is the fact that Nixon was a stage actor while at Whittier College. A fact that connects him and Ethel Rosenberg—whom he romanticizes before he ever meets her. He’s bumbling, self-righteous, ambitious and a bit cowardly, but he knows the forces that have shaped him. He understands himself as a player in a drama with a role to play, even if it’s not always the most popular role.

It is then the “Public” that is so scorned in this book. Both the people and their need for exhibition are central to Coover’s excoriation. The election of Donald Trump was a public statement from a forgotten mob gathered in whatever the Rust Belt’s equivalent of Times Square may be, declaring that they wouldn’t be subjected to politics as usual. They wanted the man they’d seen on TV, exorbitantly wealthy and with simple catchphrases: “You’re Fired,” “Build the Wall,” “Lock Her Up.” Coover’s Soviet Phantom has transformed into the boogeymen of ISIS and immigrants and the brash and mouthy Donald Trump was the Uncle Sam that would stand up to them. If there is any one character that is most like Donald Trump it is indeed Uncle Sam—the Supreme Id of America who enunciates in a disarming folksy voice that always bespeaks the terror abroad. Uncle Sam’s brand of patriotism is culturally fascistic, coated in a religious zealotry: Americans are the freedom loving Sons of Light grappling with the cruel Soviet Sons of Darkness. The novel’s ancestors, ultimately, are works like Hawthorne’s The Scarlett Letter and Miller’s The Crucible—the latter of which is even name checked in the book. Hysteria is rampant.

In between Nixon’s chapter is a panoply of world events and famous figures, overstuffing the page like the chyrons and twelve talking heads on cable news. There are so called “Intermezzos” that render events in the form of stage scripts, operas, and poems. What Coover displayed was that straightforward narrative was no good. There has to be a pomp and circumstance to everything that Americans do. Our campaign trail is reported as less of an investigation of policies and more of a serial tracking of Page-Six gossip.

Tom LeClair argued, in an essay for the Daily Beast this January, that Coover’s The Public Burning anticipated Donald Trump. But rather than anticipate, perhaps it reveals certain narratives and archetypes that have always existed in America. As Faulkner said, “Most men are a little better than their circumstances give them a chance to be.” Donald Trump did not come out of a vacuum. Large forces stretching back to at least the Goldwater campaign, and the birth of the Southern Strategy, allowed him to exist. Donald Trump is much more of ourselves than we like to admit, but that Coover so directly scorned four decades ago. Trump’s campaign was full of drama, intrigue, fear, humiliation, but it was always interesting. It was always something new. It was always eminently captivating. Coover was not just anticipating Donald Trump or a Trump-like figure, he was telling the American Public that their personal conscience could best be understood by what spectacle there was to watch. America exists to be audacious. Which leads us to wonder: what fresh audacity is coming this summer?

Sonny Franks

May 26, 2017 at 9:37 pmWell done, sir!!