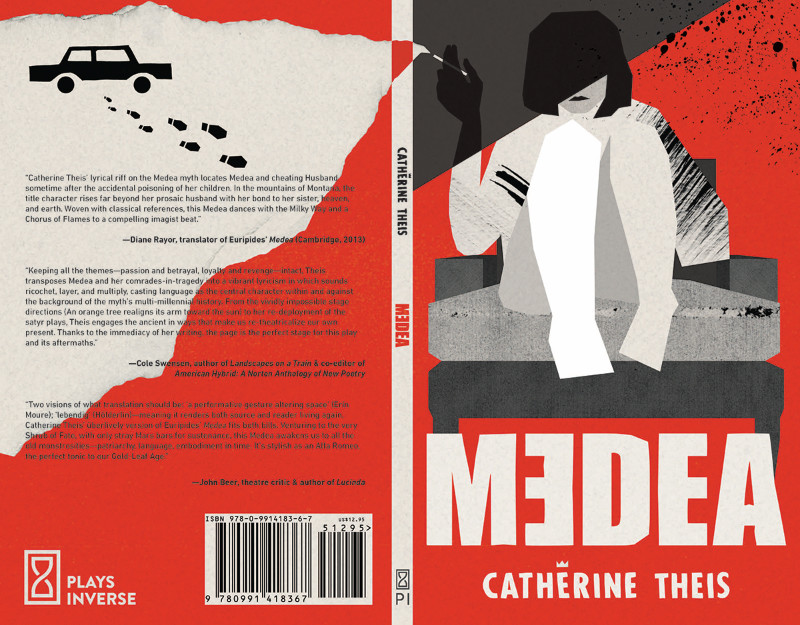

Book Review: Medea by Catherine Theis

Catherine Theis’s Medea convincingly straddles the boundary between poetry and play, neither entirely one nor the other. Theis’s language is wild, unconstrained; she never allows formal convention to inhibit her writing, rather using it as a scaffold from which to leap to greater heights. From the beginning, it’s unclear if or when exactly one is to begin reading the work as poetry; even the “Cast of Characters” opens to poetic interpretation. Like the volcanic eruption alluded to throughout the work, Medea explodes out of its confines; the violence inherited from the myth permeates the very structure of the play, with its impossible-to-follow stage directions and the assertion in the staging notes that the play requires “an unwilling audience”—a paradox. Some “spoken” lines are elided, struck through; the set is described in unlikely terms. The practicalities of staging give way to passionate artistry. It is impossible to read the book without imagining the play, and yet the play remains itself impossible. A chorus member says their “experience / is theatrical, not actual” and this awareness of life as artifice, of the life of myth, pervades the entire “play.”

While readers familiar with the Medea myth will appreciate and understand more of the subtleties in the text than a novice reader, Theis’s Medea stands on its own as a possible introduction to the story, especially given its adaptation to modern terms. The most difficult portion of the book is the satyr plays at the end; without a grounding in Greek theatrical tradition, this inclusion may be too jarring to be easily understood. Even with knowledge of Greek theatre, the satyr plays stand out as an unusual choice. Theis claims in the introduction that they are “to brighten moods” after the conclusion to Medea’s story. Certainly the transition between the two sections is jarring, deliberately, with the most ribald of the satyr plays immediately following the melancholic ending to Medea, but upon the close of the final satyr play, the two moods have become inexorably entwined, and not particularly bright. The interplay of passion, sex, and violence in the larger story is disturbed and reexamined by these short “plays” (really some of the most poem-like poems in the book) at the end, opening the work to a broader variety of readings and further stretching the work’s genre.

Theis brings fresh, new life to an ancient story. As a character, Medea exists as a kind of echo of herself, seeming to recall all her various incarnations from Euripides to this one, in present day Montana, despite here living through her betrayal yet again. She already recalls poisoning her children; on the next page, she hints at a new pregnancy. The banal, quotidian marital life Theis paints of Medea and her unnamed husband is a thin veneer over the boiling pit of Medea’s passions, her rage rekindled with each reincarnation. It breaks through her language, destroying her ordinary conversations with strange prophetic images. No other character in the work has Medea’s force of personality; the whole world of the play turns on her. Despite her wrath, Theis’s Medea also burns with love, and the dual choruses of The Milky Way and The Flames allow for reflections of this double nature, the passion that leads to love flowing from the same well as that which enables murder. Theis explores in this way the nature of myth, murder, and womanhood, imbuing her iteration of Medea with the depth of all which came before. Medea is truly an ecstatic book, in the Dionysian sense.

Phoebe Merten is currently working towards her MFA in Creative Writing and MA in English at Chapman University, the natural followup to her BFA in Theatre Arts with an emphasis in Lighting Design. She writes poetry and prose and tends to disregard the distinction between the two. She prefers precise and loving use of language, with each word collected and fondled like a jewel. Her current projects of varied genre focus on love, connection, and the inherent dangers therein.

Phoebe Merten is currently working towards her MFA in Creative Writing and MA in English at Chapman University, the natural followup to her BFA in Theatre Arts with an emphasis in Lighting Design. She writes poetry and prose and tends to disregard the distinction between the two. She prefers precise and loving use of language, with each word collected and fondled like a jewel. Her current projects of varied genre focus on love, connection, and the inherent dangers therein.

Featured Image: provided by SAIC licensed under CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0