The Once and Future Site

Candice YaconoThe Once and Future Site:

The History and Archeology of Tintagel, Cornwall

Excavation lead Jacky Nowakowski measures the width of a trench at Tintagel in July 2017. Photo taken by the author.

“Hard by was great Tintagel’s table round and there of old the flower of

Arthur’s knights made fair beginning of a nobler time.” – Thomas Hardy

The Once and Future Site: The History and Archeology of Tintagel, Cornwall

William Trost Richards, Tintagel, 1881, Watercolor, National Academy Museum, New York, public domain.

Trade emporium? Royal complex? Tax center? Pirates’ den?

The latest excavations at the Tintagel Castle site in Cornwall, England have revealed its critical role along Mediterranean trade routes in the post-Roman era, but they present more questions than answers. Evidence has emerged suggesting that the complex was a hugely important center in post-Roman Britain, but what function did it serve? Who lived within its walls and took part in lavish banquets in which diners ate oysters served on fine Samian ware suited for a king’s table, while drinking wine from Merovingian glass goblets?

These luxurious finds, as well as writing etched into the site’s very walls, hint at a much more urbane lifestyle than previously believed possible following the departure of the Romans. They also have called into question whether the supposed “Dark Ages” in England really were so dark.

A Sense of Place

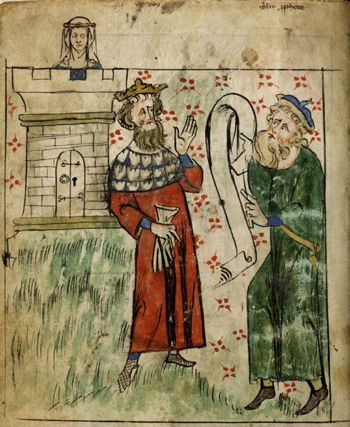

Uther and Merlin in front of Tintagel. Royal 20 A II, Peter of Langtoft and others, parchment codex, c. 1307 – c. 1327, British Library collection, public domain.

Tintagel is an outcropping of headland off the northern coast of Cornwall, a peninsula in southwest England. It resembles an island because the narrow neck of land joining it to the mainland has eroded over the centuries. Today the headland can only be accessed via hundreds of ascending and descending steps and a bridge over the remains of the causeway. The archeological site is divided in two: the medieval mainland castle ward and the headland on the “island,” which also contains evidence of a substantial post-Roman settlement.[i]

The site’s fame began in the 12th century, when cleric and historian Geoffrey of Monmouth claimed Tintagel as the birthplace of the legendary King Arthur in his “Historia Regum Britanniae.” The story went that the High King Uther became desirous of the Lady Igerna, the lovely wife of Gorlois, one of his nobles. He tasked the enchanter Merlin to transform him through magical arts to resemble Gorlois, clandestinely entered Tintagel, and lay with Igerna, who conceived Arthur.[ii]

In the 13th century, an unscrupulous noble who owned the land sought to make it a lucrative pilgrimage location by advertising its links to the beloved king.[iii] While this claim has been debunked, Tintagel’s association with Merlin, Arthur and Camelot persists, as promoted by writers like Tennyson.

‘No site like it in the whole of Britain’

The steep descent and approach from the mainland ward to the “island” in July 2017. Photo taken by the author.

Cornwall was home to the Dumnonii tribe in pre-Roman Britain.[iv] Recent excavations at Tintagel have uncovered Mesolithic and Neolithic artifacts. During the Roman period, Roman presence was thought to be minimal in the region, which is located to the west of the Roman legionary fortress and town of Isca Dumnoniorum (modern-day Exeter). However, two Roman milestones were discovered in the area of Tintagel.[v]

The site has seen sporadic excavations over the past 80 years. Both the quantity and quality of the finds suggest that Tintagel was a major regional player in the trade of the 5th to 7th centuries.

A post-Roman “great ditch” on the mainland side of the complex suggests the local population may have taken a defensive stance. The only approach was via a narrow entry under a cliff, which could easily be protected.

“So it was defending something, but what?” said Win Scutt, Assistant Properties Curator (West) for English Heritage. “We don’t understand the early days of state formation enough to know what it would be used for. But there’s no site like it in the whole of Britain.”[vi]

From there, there was little evidence of habitation or use until it was mentioned by Geoffrey of Monmouth. His “Historia Regum Britanniae” (considered for centuries to be factually accurate, but since disproven) stated that the fabled King Arthur was conceived at Tintagel.[vii]

William of Newburgh wrote regarding Monmouth in around the year 1190 that “it is quite clear that everything this man wrote about Arthur and his successors, or indeed about his predecessors from Vortigern onwards was made up, partly by himself and partly by others, either from an inordinate love of lying, or for the sake of pleasing the Britons.”[viii]

“A Coloured Plan, or Bird’s Eye View of ‘Tindegal Island’ or Tintagel Castle, near Bossiney, on the North Coast of Cornwall.” Circa 1560. British Library, public domain.

Although there is no conclusive evidence that Arthur, the “Once and Future King,” ever lived, his name is indelibly tied to the site due to its connections with Richard, 1st Earl of Cornwall. One of the richest men in Europe, second son of the infamous King John of the Robin Hood legends and brother of Henry III, the Norman Richard was given the duchy of Cornwall by his brother as a sixteenth birthday present in 1225. Within a decade, he had traded lands for Tintagel and built a castle there that was more of a folly than a defensive structure.[ix]

Richard had hoped, it is believed, that the new castle would serve two purposes: To help him gain the trust of the Cornish and to link his name with the wildly popular Arthurian legends (then believed to be fact) propagated by Geoffrey of Monmouth a century prior.[x] Regardless of the reasons, the castle quickly fell into disrepair.[xi]

The archaeology of the site suggests two main periods of occupation: the immediate post-Roman period and that of this 13th-century castle.[xii] There are rare examples of occupation in between these times, such as an 11th-century chapel. The castle was repaired and improved in the 14th century, but was fully abandoned within 300 years.[xiii]

The site was mentioned by John Leland in his famed Itinerary during the Tudor era, but had fallen into total disuse by the Elizabethan era.[xiv]

The adjacent town of Tintagel was known as Trevena until the turn of the 20th century, when Tennyson rekindled popular interest in the area in his “Idylls of the King.”[xv] The King Arthur’s Great Halls tourist attraction opened in 1933, the year the first archeological excavations at the site began, and Tintagel again took up its place as a center of Arthurian interest.[xvi]

A view to the mainland from Tintagel’s eastern terrace. Photo taken by the author.

Today the site is kept in guardianship for the duchy of Cornwall by English Heritage.[xvii] The property’s custodians are careful to preserve their site for future generations. A planned footbridge, designed using a cantilever approach that minimizes the impact on the site’s archaeology, will allow increased access from the mainland to the “island” ward to more of the estimated 15 percent of visitors who cannot navigate the site’s many stairs.[xviii]

Other conservation methods include the use of inert local material to repair paths, to prevent the archaeology from becoming contaminated. But the whim of nature is always at the back of the custodians’ minds. Large swathes of the headland and castle have already plummeted into the Atlantic since the days of the Dumnonii.[xix]

“This whole castle will one day fall into the sea. It could happen in a thousand years. It could happen in a hundred years. It could happen tomorrow,” Scutt said.[xx]

Fit for a King?

Theories regarding the function of post-Roman Tintagel have changed dramatically since the initial excavations of the site. The archaeologist C. A. Ralegh Radford, in his pioneering 1930s work, excavated and found several dwellings and other structures, primarily on the headland’s eastern terraces and summit. He theorized that the Tintagel of the 5th to the 7th centuries likely served as a prosperous but isolated monastic settlement for an elite group of monks[xxi]. Unfortunately, his home in Exeter was bombed during the Blitz in 1942, and the paper records of his excavation were lost before he was able to publish his findings.[xxii]

Radford’s excavations focused on “restoring” the buildings he found, rather than carefully recording the site. The restorations were somewhat fanciful, rather than accurate. “Guardianship then was about making ruins presentable,” Scutt said. “Radford showed this was an important place, but he wasn’t doing it in a scientific way; he was just clearing rubble.”[xxiii]

Radford’s theory that the site was a remote Christian monastery was called into question when it was discovered that the site contained the largest quantity of imported glass and pottery in the whole of Britain and Ireland.[xxiv] A major breakthrough came by chance in 1983, when a peat fire exposed the remains of many buildings throughout the headland; to date, more than 100 building foundations have been found through subsequent excavations and earthwork surveys, including on the eastern and south terraces, as well as the summit of the headland. All of these except the aforementioned chapel appear to be firmly early medieval, established in the centuries immediately following the departure of the Romans from Britain’s shores.[xxv]

A smaller-scale excavation in the 1990s, led by Charles Thomas of Glasgow University, opened up Radford’s trenches to confirm his data. This led to major revisionism about the function of the site. The extant finds were re-examined. Radiocarbon dating, a technology which was not available to Radford’s team, confirmed that the site was used as early as the late Roman occupation in the 4th century through the 7th century.[xxvi]

Something Old, Something New

New excavations have uncovered more information—not just about Tintagel, but about the whole Mediterranean region.

The recent excavations of 2016, 2017, and 2018 are part of the five-year Tintagel Castle Archaeological Research Project (TCARP) led by English Heritage, which commissioned a team from Cornwall Archaeological Unit to work with specialists to investigate the post-Roman settlement. The project marks the first excavations of the majority of the site.[xxvii]

TCARP already has unearthed a wealth of evidence that points to Tintagel being a high-status (and perhaps royal) Dumnonian site with substantial trading ties to the Mediterranean.[xxviii]

In 2016, following ground penetrating radar and laser scanning, four small trenches were dug: two on the steep southern terrace, which were christened Geraint and Mark in a nod to Dumnonian history, and two on the eastern terrace, which were named Tristan and Isolde. The Tristan trench on the eastern side revealed a substantial revetment wall, about 1 meter wide, which held a terrace. However, no buildings were found. On the southern side, the Geraint trench led to the discovery of several stone walls, paving, and a flagged floor. The Mark trench also contained a revetment wall.[xxix]

“Such structural evidence is unlike any of the standing ruins on the headland that the visitor sees today,” the excavation report read.[xxx]

Among the artifacts found in all the trenches were roughly 200 sherds of imported Mediterranean pottery and pieces of “high status” imported glass, some of which were etched or otherwise decorated. Both sites on the headland were confirmed to have been in use in the early medieval period as a result of these discoveries. The artifacts suggest Byzantine-era trade links to what are now France, Spain, northern Africa, and the eastern Mediterranean.[xxxi]

In addition to the artifacts and ecofacts, the soil was sieved in both wet and dry form. As a result, pollen and seed samples, bones, and charcoal were added to the footprint of the site.[xxxii]

Subsequent excavations focused on a cluster of buildings on the southern terraces, which were seen in 2017 for the first time in more than a millennium.[xxxiii] They shed further light on the post-Roman world of the Dumnonii.

Slate paving and other architectural details, as well as high-end domestic artifacts, suggest a well-fed, urbane population. The artifacts found include oysters, Merovingian glass, amphorae from the eastern Mediterranean, and fine red slipware that would have been used at the highest tables.[xxxiv]

Carl Thorpe displays a potsherd found at Tintagel in July 2017. Photo taken by the author.

Finds from the summer 2017 dig hint at Neolithic occupation; in addition, a Mesolithic flint form attracted the team’s attention.[xxxv] But the site’s bread and butter is post-Roman artifacts and ecofacts.

“Ninety percent of the material finding is Mediterranean,” excavation finds supervisor and CAU Archaeologist Projects Officer Carl Thorpe said. “We have only excavated maybe two percent of the site, but there is more of this type here than anywhere in Western Europe.”[xxxvi]

One of the first pieces the team found in 2017 was a piece of furnace lining, suggesting metalworking was performed onsite. An enigmatic blue bead might have Egyptian provenance. A bit of green glass that may be a sherd of an Anglo-Saxon claw beaker was found in July; Thorpe said such a discovery had never been made at Tintagel. Other finds included an amphora sherd with Greek lettering on it.[xxxvii]

In 2018, archeologists uncovered a two-foot-long stone, likely used as a window ledge, that was littered with graffiti-like 7th-century etchings including Christian symbols, Roman names like Tito (Titus), Celtic names like Budic, Latin phrases like “fi li” (son) and “viri duo” (two men), and Greek letters.[xxxviii]

A 7th-century stone covered in etched writing. Photo by the Press Association.

Some posit that the carvings may have made by a young student learning to write; others speculate, due to the high quality of the writing itself, that it was etched by a scribe. Either way, the presence of such writing suggests wealthy or royal inhabitants who were privileged enough to host someone who could write.

This discovery comes on the heels of another stone found on the site in 1998 that had the name “Artognou” written on it, which set off a frenzy of speculation that it referred to the legendary King Arthur.

While there is no historical proof of the existence of Arthur, at Tintagel or elsewhere, Thorpe posited that the headland may have been occupied seasonally by a royal family that went on “progress” to other locations throughout the year; finds suggesting this have been discovered at St. Michael’s Mount on the southern coast of Cornwall.[xxxix]

Throughout most of the island, only about 24 inches of soil may contain archaeology; below it is rock. The pottery found so far seems to be concentrated near the later medieval castle on the west side of the headland, rather than on the top of the island.[xl]

The archaeological evidence does not point to tin exports during that time, Scutt said, although nearby adits attract the attention of scholars. It is far more likely that the region exported agricultural products, like wool, leather, and organic goods.[xli]

A Foregone Conclusion?

With work still ongoing at the site, there are no conclusions as to the purpose of post-Roman Tintagel. However, theories abound.

Scutt, a theoretical archaeologist, said his role is to determine how far one can stretch available frameworks and data to fit other scenarios. To that end, he provided various possible theories for Tintagel’s function, including a high-stakes political site (potentially royal), similar to Thorpe’s aforementioned suggestion; a tax center to collect from those traveling down the coast or through the channel; or a defensive center. Other, more far-flung possibilities also exist. These include a possible piracy base, given that piracy posed a major problem in the post-Roman world. Or, Scutt added, could Tintagel have served as a refugee center for those escaping the tumult of the post-Roman power vacuum? A wealth of Syrian pottery has been found in the excavations, drawing parallels to today’s world. He also suggested the possibility that the rapid decline of the site was due to a 7th-century outbreak of bubonic plague.[xlii]

Whatever is yet to be discovered at Tintagel, it is clear from current evidence that the Dumnonii leadership thrived at least for a short period following the withdrawal of Rome. The liveliness of the trade routes of post-Roman Europe and the Mediterranean suggests a far more vibrant, connected “Dark Ages” world than previously believed.

Works Cited

[i] Barrowman, Rachel, Batey, Colleen, and Morris, Christopher. “Excavations at Tintagel Castle, Cornwall, 1990–1999,” Reports of the Research Committee of the Society of Antiquaries of London, 74, London, 2007. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0254.2009.00246.x.

[ii] Geoffrey of Monmouth, Bishop of St. Asaph. “The History of the Kings of Britain: An Edition and Translation of De Gestis Britonum (Historia Regum Britanniae).” Translated by Neil Wright. Boydell Press, Woodbridge, UK, 2007.

[iii] Ditmas, E. M. R. “A Reappraisal of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Allusions to Cornwall.” Speculum, vol. 48, no. 3, The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Medieval Academy of America, July 1973, pp. 510-524. JSTOR, doi:10.2307/2854446.

[iv] Pearce, Susan M. “The Cornish Elements in the Arthurian Tradition.” Folklore, vol. 85, no. 3, Taylor & Francis, Ltd. on behalf of Folklore Enterprises, Ltd., Autumn 1974, pp. 145-163. Accessed on JSTOR. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1260070.

[v] Collingwood, Robert. “Roman Milestones in Cornwall.” The Antiquaries Journal, 4(2), 1924, pp. 101-112. Accessed at https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.282962.

[vi] Scutt, Win. Personal interview, July 30, 2017.

[vii] Geoffrey of Monmouth, “History.”

[viii] Cunliffe, Barry. “Britain Begins.” Oxford University Press, 2013, p. 9. Collection of the University of California, Irvine.

[ix] Barrowman, Rachel, Batey, Colleen, and Morris, Christopher. “Excavations.”

[x] Ditmas, E. M. R., “Reappraisal.”

[xi] Radford, C. A. Ralegh, “The Excavations at Tintagel.” The Antiquaries Journal, vol. 14, no. 01, 1934, pp. 64–65.

[xii] Thomas, Charles. “Tintagel Castle.” Antiquity, vol. 62, no. 236, 1988, pp. 421–434.

[xiii] Nowakowski, Jacky, and Gossip, James. “Tintagel Castle, Cornwall Archaeological Research Project TCARP16 Archive and Assessment Report – Excavations 2016.” Cornwall Archaeological Unit, 21 June 2017. Accessed at http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/content/AboutUs/2241346/2770808/3070056/3408851.

[xiv] Toulmin Smith, L. (ed). “The Itinerary of John Leland on or about the Years 1535–1543, vol I.” London, 1907, pp. 177, 316-17. Accessed at https://archive.org/details/itineraryofjohnl01lelauoft.

[xv] Snyder, Christopher A. “An Age of Tyrants: Britain and the Britons, Parts 400-600.” Penn State Press, Nov 1, 2010, p. 184. Collection of Irvine Valley College.

[xvi] Ashton, Gail. “Medieval Afterlives in Contemporary Culture.” Bloomsbury Publishing, Mar. 12, 2015, p. 207. Collection of the University of California, Irvine.

[xvii] Nowakowski, Jacky, and Gossip, James, “Tintagel Castle.”

[xviii] English Heritage. “Tintagel Castle – Winner of New Bridge Competition Announced.” 23 March 2016. Accessed at http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/about-us/search-news/tintagel-bridge-competition-winner-announced.

[xix] Scutt, Win, interview.

[xx] Scutt, Win, interview.

[xxi] Radford, C.A. Ralegh, “Excavations.”

[xxii] Gilchrist, Roberta. “Courtenay Arthur Ralegh Radford.” Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the British Academy, XII, British Academy, 2013, pp. 341-358. Accessed at http://www.academia.edu/11336404/Courtenay_Arthur_Ralegh_Radford.

[xxiii] Scutt, Win, interview.

[xxiv] Thomas, Charles, “Tintagel Castle.”

[xxv] Nowakowski, Jacky, and Gossip, James, “Tintagel Castle.”

[xxvi] Thomas, Charles, “Tintagel Castle.”

[xxvii] Nowakowski, Jacky, and Gossip, James, “Tintagel Castle.”

[xxviii] Nowakowski, Jacky, and Gossip, James, “Tintagel Castle.”

[xxix] Nowakowski, Jacky, and Gossip, James, “Tintagel Castle.”

[xxx] Nowakowski, Jacky, and Gossip, James, “Tintagel Castle.”

[xxxi] Nowakowski, Jacky, and Gossip, James, “Tintagel Castle.”

[xxxii] Nowakowski, Jacky, and Gossip, James, “Tintagel Castle.”

[xxxiii] Thorpe, Carl. Personal interview, July 30, 2017.

[xxxiv] Thorpe, Carl, interview.

[xxxv] Thorpe, Carl, interview.

[xxxvi] Thorpe, Carl, interview.

[xxxvii] Thorpe, Carl, interview.

[xxxviii] Krakowka, Kathryn. “Second inscribed stone found at Tintagel.” Current Archaeology, no. 342, August 2018. Accessed at https://www.archaeology.co.uk/articles/second-inscribed-stone-found-at-tintagel.htm.

[xxxix] Thorpe, Carl, interview.

[xl] Scutt, Win, interview.

[xli] Scutt, Win, interview.

[xlii] Scutt, Win, interview.

Provenance: Submission

Candice Yacono is an MFA candidate at Chapman University, where she studies creative writing. She freelances as a feature and travel writer, editor, and graphic designer for clients worldwide, including the Los Angeles Times, Fodor’s Travel, and the U.S. Department of State. Candice holds a BA in journalism and international relations from San Francisco State University. She has no time for your tomfoolery.

Candice Yacono is an MFA candidate at Chapman University, where she studies creative writing. She freelances as a feature and travel writer, editor, and graphic designer for clients worldwide, including the Los Angeles Times, Fodor’s Travel, and the U.S. Department of State. Candice holds a BA in journalism and international relations from San Francisco State University. She has no time for your tomfoolery.

Michel A Kramer

December 7, 2018 at 7:21 pmFond memories from travel a well as harking back to days at U of Cincinnati.