Straying from Popular Memory: Examining the War Experiences of Berry Robison in Vietnam

Cameron Carlomagno

Whereas World War II is considered the “good war” in the American psyche, the Vietnam War is generally seen as the opposite. Largely remembered as a war of gross injustice fought by aggrieved Americans, Vietnam has become an example of American imperialism and failed military ventures.[1] The United States had maintained a presence in the country since 1950, helping the French to reassert control over their colony. It was not, however, until a decade later that the American public became acutely aware of the war effort in Vietnam. Within a few short years, the public gradually turned against the war, culminating in mass disapproval in the years after the 1968 Tet Offensive, a series of coordinated attacks in South Vietnam by the National Liberation Front (NLF)—otherwise known as the Vietcong—and the North Vietnamese Army (NVA).

Captured on film by American journalists in South Vietnam at the time, Tet was replayed on the screens in American homes, showing the horrors of war and contradicting politicians’ assertion of American victory in Vietnam. One of the most famous photographs coming out of the event, memorializing the Tet Offensive and the Vietnam War, was Eddie Adam’s Pulitzer Prize-winning picture of a South Vietnamese police chief shooting a captured Vietcong agent at point-blank range.

Militarily Tet was a victory for the United States, but journalists in the country nonetheless highlighted the horrors of war, specifically noting the brutality committed by the American and South Vietnamese armies.[2] As a result, Tet helped solidify the popular memory of Vietnam as a war of American imperialism and failed military ventures.[3] With waning public support, Tet set in motion a series of political events that eventually led to American withdrawal in 1973.

Yet, it is important to acknowledge the potential differences between popular memory and individual memory.[4] While popular memory recalls the Vietnam War as a highly divisive period, and particularly anti-war in its sentiment, when exploring individual memory more nuanced opinions surrounding the war appear. One example of this is seen through the letter correspondence of Berry “Robie” Robison, a member of the 101st Airborne Division, who relays his opinion about the war to his wife Christine while in Vietnam.

Deployed to Vietnam from latest March 1968 until June 1969, Robison primarily focused on his continual dedication to fighting in Vietnam, as well as support for the ideological purposes of American intervention in the country. That said, he also expressed his frustration over the course of the war, particularly blaming American politicians for the failures of the war effort. I contend that Robison’s correspondence provides a more nuanced perspective of the Vietnam War during this period, which is underrepresented in the existing popular memory of Vietnam.

Many historians take the position that Tet played a significant role in shaping the discourse surrounding the war in Vietnam, ushering in the end of the war in Vietnam and directly impacting the policies surrounding the war. Yet, there is a noticeable split between scholarship that demonstrates the strength of the divide between those supportive of and opposed to the war. For instance, David Cortright’s Soldiers in Revolt: GI Resistance During the Vietnam War and Meredith H. Lair’s Armed with Abundance: Consumerism & Soldiering in the Vietnam War discuss the war effort following the initial attack in January 1968 from the perspectives of both combatants and non-combatants, specifically touching upon the overarching poor morale amongst soldiers in this stage of the war.[5] Thus, supporting the anti-war popular memory of the Vietnam War during this period.

In contrast, Don Oberdorfer’s book Tet: The Turning Point in the Vietnam War, and David F. Schmitz’s The Tet Offensive: Politics, War and Public Opinion, qualify the popular memory of Tet.[6] Although many scholars depict the attack as a singular event that served as the turning point of the war, both Oberdorfer and Schmitz assert that the collapse of the war effort in Vietnam was made of more than just a singular moment. As a result, creating more complex conceptions of the war in Vietnam.

Finally, Ronald H. Spector’s work After Tet: The Bloodiest Year in Vietnam, and Peter Kindsvatter’s American Soldiers: Ground Combat in the World Wars, Korea and Vietnam, both challenge the narrative of the Tet Offensive.[7] Spector believes that Tet signaled a renewal of fighting and that the months following Tet were more decisive in ending American intervention in Vietnam than the Tet Offensive. Kindsvatter also confronts the popular memory of the Vietnam War by illustrating the diversity of experiences within the war, providing evidence that refutes the popular conception of the Vietnam soldier as the resentful draftee.

Collectively, these scholars illustrate the various aftermath reactions following the initial attacks of the Tet Offensive. Beyond examining the range of responses to the news from Vietnam, these authors allude to how the reaction contributed towards to either an anti-war or pro-war stance. This essay contributes to this conversation by providing a narrative that challenges popular conceptions of the Vietnam War, illustrating the complexity of the Vietnam War experience.

Historians have debated the value of using letters to gain an inside perspective of the soldier’s experience during war since they are susceptible to censorship, bias, or misapprehension. In his seminal work, The Great War and Modern Memory, Paul Fussell devotes space to illustrating the drawbacks of using letters to gain an accurate account of war. Focusing on letter writing during the First World War, Fussell asserts that, “any historian would err badly who relied on letters for factual testimony about the war,” because of the self-censorship and the governmental censorship of soldier correspondence.[8]

That said, it is important not to take these arguments against letters as a standard rule when exploring the soldier’s experience. When evaluating the usefulness of letters, recognizing the individuality of each collection is crucial as each letter is written with an exact purpose, and the difficulty is in understanding the intention. While acknowledging the possible shortcomings of using letters in her article “War Letters,” Martha Hanna nevertheless argues that, “the correspondence of front-line soldiers…when read in its entirety, is extraordinarily revealing not only for what it said about the war, but also for what it tells us about how combatants remained connected psychologically and emotionally to the families they had left at home.”[9]

Overall, even though there is an argument against using letters, they nonetheless present important details when analyzing the soldier’s experience. Not only do they provide information on the war experience, but they also supply background information about the individual and society during the time. Moreover, instead of assuming that all letters possess the faults highlighted by Fussell, it is important to evaluate each set of correspondence on a case-to-case basis. Therefore, letters should not be omitted because a possibility that they may not be the most factual retelling of the war.[10] Robison’s letters are just one example of many of the strengths that such correspondence supplies. While there is a considerable degree of information about Robison’s experience missing from his letters, they nevertheless provide ample details concerning the various opinions that existed in this period.

There are certain assumptions that can be made about Robison’s prior life based on clues throughout the letters. As he was twenty-two—he had a birthday sometime during his tour, turning twenty-three—in the beginning of his letters, it can be subsequently inferred that he was born a year or two after the end of World War II. As a result, he was probably impacted by the war stories he grew up hearing. Furthermore, based on his age it can be surmised that he had at most a high-school education. This is supported in a letter written in May 1969 when he expressed his frustration over the college student protests surrounding the war, “When I tried to go to college, I had no money, now kids are given the right to go to college, money + all and what do they do.”[11]

Based on his unit’s history—the 3rd Battalion, 187th Infantry Regiment (Airborne)—and his letter collection, Robison was likely deployed to Vietnam sometime between December 1967 and March 1968.[12] While it is unknown whether he was drafted, considering he was part of the 101st Airborne Division, which required special and extensive training, it is more likely that he volunteered. Even though Robison did not extensively reflect upon his specific location, his letters do provide a basic idea of his movements throughout the country. On August 13, 1968, Robison wrote “in answer to your question I was not on that operation near Saigon. I guess I can tell you now, that I received a purple heart in action near Cu Chi Northwest of Saigon.”[13] The next time, Robison indicated his location is in September, explaining another combat mission where his unit was “down between Trang Bang and Tay Minh City, when all hell broke loose.”[14] As his tour continued, his unit moved farther north towards the Demilitarized Zone, spending some time at “Camp Eagle, which is right in between Hue + Phu Bai.”[15] Before finally getting pulled off the front lines at the end of his deployment, he was sent into the A Shau Valley.

Robison’s movements and combat missions throughout Vietnam substantiates Spector’s thesis that “The nine months following LBJ’s historic speech saw the fiercest fighting of the war.”[16] Since Robison was engaged in continual combat following the initial attacks of the Tet Offensive, it is conceivable that he viewed the war in a different light than those on the home front. While the Tet Offensive was viewed as a singular event to Americans back home, those fighting understood it to be a series of attacks that lasted for months rather than days or weeks.[17] Plus, “Over the next nine months, while attention in the United States was focused almost entirely on election year politics and the hope of a peace settlement in Paris, Americans in Vietnam would lift the siege of Khe Sanh and launch a counteroffensive.”[18]

Although Tet is usually viewed in terms of a rapidly decreasing morale for those at home and in Vietnam fighting, the opposite occurred for Robison. Instead, the continual fighting in Vietnam reinforced his support for the war effort. This is seen in his correspondence repeatedly. For instance, on October 14, 1968, Robison wrote, “I could never be as proud of the job that we are doing over here, no matter what.”[19] This sentiment was expressed in a letter that also detailed a recent combat mission, Robison explaining that during an eighteen-day period “My company was hit hard in the beginning from all directions, we reconsolidated and called in artillery, tac air + gun ships [sic]. We closed with and destroyed the S.O.B., at the time I had no one to turn too [sic], but the operation was a complete success according to military standards.”[20] Such military accomplishments, especially when they are reinforced by military training and societal expectations when growing up, understandably incites some amount of pride.[21] This sentiment is further relayed in a letter written on November 8, 1969, when Robison expressed that, “I am physically worn, mentally there is always something to worry about, but I find it is a highly rewarding job and I am extremely proud of the unit I am in.”[22]

Robison also makes more broad statements concerning his support for the war through his letter correspondence. In May 1969, Robison asserted, “I only believe in one thing and that is the Democracy that the United States of America has provided for her citizens. I still believe in our country ever more so now and I would come over here or anywhere that the U.S.A. deems necessary.”[23] This comment is significant as it highlights that Robison’s support for the war effort in Vietnam stems largely from his advocacy for American democratic ideals. Robison’s values, which likely existed prior to deploying to Vietnam and reinforced by the war, are the basis for his pro-war sentiment. In one of his last letters Robison declared that “I think a man should believe in something whether God, Country or what have you and be willing to die for his believe [sic], however I wonder what I would think if I hadn’t come to V-Nam.”[24] Recognizing the role that his combat experience in Vietnam potentially had in his beliefs, Robison demonstrates that it was possible for soldiers’ to maintain—or even strengthen—their pro-war position concerning Vietnam.

That said, however, Robison’s perspective is more complex than simply agreeing with the war. Those involved within the debate were often characterized as either a hawk or a dove; invoking imagery of being either staunchly pro-war or anti-war respectively.[25] Yet, Robison’s letter collection demonstrates that such categorizations are too simplistic, and probably contribute to a divide between the different sides of the war. Reflecting upon the war in his last few letters in the collection, Robison continually voiced his opinion about the failures of the war effort, specifically blaming American politicians. In a letter written on May 15, 1969, Robison told his wife that “As I sit here writing this letter, I am listening to President Nixon as he talks on the V-Nam war, to say the least I am totally confused.”[26] Although Robison never directly stated why he was mystified, it can be assumed that it is due to Nixon’s report on the current state of the war and the steps planned for the withdrawal of the armed forces. Reporting his plan for the removal of troops, Nixon stated that “Over a period of 12 months, by agreed-upon stages, the major portions of all U.S., allied, and other non-South Vietnamese forces would be withdrawn. At the end of this 12-month period, the remaining…forces would move into designated base areas and would not engage in combat operations.”[27]

In his next letter written to his wife, on May 22, 1969, Robison expressed, “Baby its funny how soldiers want to go where the fighting is, for instance end this thing by fighting in North Viet Nam [sic], but our crooked [sic] politicians couldn’t make any money if the war was over.”[28] Although the validity of this statement is unknown, it nonetheless expresses Robison’s blame on politicians for both American failures in Vietnam and the prolongation of the war, since Robison assumes that the U.S. military would be capable of ending the war if they were allowed to continue North. The one instance when Robison’s otherwise positive morale wavers was when he wrote, on May 22, 1969, “Chris all I want to do is get out of this filthy God-forsaken place + let someone else be a guinea-pig for a corrupt bunch of exploiting politicians.”[29] While the poor morale may have resulted from exhaustion, especially considering the hostile physical environment of Vietnam, this statement highlights Robison’s continual frustration with politicians.[30]

Robison continues this statement, however, by reasserting his commitment to American democratic ideals, stating “However let the U.S.A. jump in for Israel or some country that will help themselves + I will volunteer, but not for a bunch of lazy slopes!”[31] There are two important elements to acknowledge in this comment. First, it illustrates Robison’s awareness of world politics during the time, making his perspectives more nuanced than simply limited to his experiences in Vietnam. Second, the statement demonstrates the racist undertone of Robison’s opinions. Blaming the South Vietnamese for the failures of the Vietnam War is a common argument made both during and following the war, using the local population as a scapegoat for the larger failure of the United States to anticipate the resilience of the Vietnamese they were fighting. The underlying racism played a role in this argument, which Robison clearly identified with. One of the best explanations for this perception can be found in Modernization Theory, a popular theory in the United States that informed U.S. foreign policy during the Cold War.[32] The view of third world countries, such as Vietnam, was informed by the perception that the people of these countries were incapable of establishing democratic institutions, thus requiring the United States to act as an over-seeing power. The racism that exists in this theory, which Robison grew up with, likely influenced his view on the Vietnamese.

Robison’s opinion of the war, is also being impacted by the voices from the home front. While it is possible that soldiers in Vietnam were influenced by the news of anti-war protests at home, Robison had the opposite reaction. One example of this was in a letter to his wife in March 1969, telling her, “I received your letter tonight concerning your waking up in the morning to the V-NAM news, baby just react to the situation as most Americans, the war just doesn’t exist.”[33] This statement predominately alludes to Robison’s perception that those on the home front are largely ignorant of what occurred on the frontlines. Moreover, it illustrates a certain amount of contempt for those back in the United States, probably for several reasons. With the growing anti-war protests in America following the Tet Offensive, which resulted in the condemnation of soldiers in Vietnam, Kindsvatter stated that many soldiers in Vietnam “resented these attacks and hated the middle-class college crowd that perpetrated them while dodging military service with various student and occupational draft deferments.”[34]

Ultimately, Robison’s ideological support for the war in Vietnam displays an important narrative of the Vietnam War that is usually disregarded. Mentioned frequently throughout his correspondence, Robison’s perspective is largely shaped not only by a set of preconceived values, but also by his military experience. Motivated by his beliefs, his role as a leader, his comradery with other soldiers, and his overarching experiences in battles, Robison’s continual promotion of the war effort is important to recognize. Moreover, while it is sometimes assumed that anti-war protests and voices from home greatly impacted those in the war, Robison’s letters illustrate that his opinions of the war were not influenced by those dissenting opinions. If anything, the critiques probably strengthened his support for the American military venture.

This analysis of Berry Robison’s wartime experience through his letters demonstrates an important perspective on the war following the Tet Offensive. Not only does Robison remain silent on the Tet Offensive, which is commonly perceived as one of the most critical wartime events, but he also maintains a voice of support for the ideological motives for war throughout his tour. Exploring the differing view of Robison illustrates the variation of opinions that existed about the war in 1968 to 1969, which are generally ignored in popular memory. Subsequently, Robison’s wartime experience questions which stories are incorporated into memory and which are excluded. Additionally, the public memory of war oftentimes has the potential of shaping the soldier’s experience reintegrating back into society. Considering Vietnam Veterans are particularly remembered for their struggles with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, author Johnathan Shay’s words, “Support on the home front for the soldier, regardless of ethical and political disagreements over the war itself, is essential,” are exceedingly important.[35] Even though the Vietnam War will continually be remembered for its violence, destruction and anti-war protests, it is nevertheless also important to recognize the experiences of those like Berry Robison.

[1] For further discussion around the memory of the Vietnam War, see Patrick Hagopian, The Vietnam War in American Memory: Veterans, Memorials, and the Politics of Healing (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2009).

[2] For further explanation of United States’ media interpretation of the Tet Offensive, see Peter Braestrup, Big Story: How the American Press and Television Reported and Interpreted the Crisis of Tet 1968 in Vietnam and Washington (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983).

[3] In the article Cultural Trauma, Collective Memory and the Vietnam War, authors Ron Eyerman, Todd Madigan and Magnus Ring note that following Tet mass media became an outline for journalists, artists, authors, etc. to report on the failures of American intervention in Vietnam, as well as express anti-war sentiment. Thus, popular culture through such mediums supported a rather negative perspective of the war. From, Ron Eyerman, Todd Madigan, and Magnus Ring, “Cultural Trauma, Collective Memory and the Vietnam War” Croatian Political Science Review 54, no. 1-2 (2017): 27.

[4] For definitions of collective memory, individual memory and popular memory, see The Collective Memory Reader, ed. Jeffrey K. Olick, Vered Vinitzky-Seroussi, and Daniel Levy, (United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2011).

[5] David Cortright, Soldiers in Revolt: GI Resistance During the Vietnam War (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2005); Meredith H. Lair, Armed with Abundance: Consumerism & Soldiering in the Vietnam War (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2011).

[6] Dan Oberdorfer, Tet: The Turning Point in the Vietnam War (New York: Da Capo Press, 1971); David F. Schmitz, The Tet Offensive: Politics, War and Public Opinion (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, INC., 2005).

[7] Ronald H, Spector, After Tet: The Bloodiest Year in Vietnam (New York: Vintage Books, 1993); Peter Kindsvatter, American Soldiers: Ground Combat in the World Wars, Korea and Vietnam (Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 2003).

[8] Paul Fussell, The Great War and Modern Memory (London: Oxford University Press, 1975), 183.

[9] Martha Hanna, “War Letters: Communication between Front and Home Front,” 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berline, Berline 2014-10-08. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15463/ie1418.10362.

[10] For more information regarding the debate in utilizing personal testimonies and memory regarding the Vietnam War, see Patrick Hagopian, “Oral Narratives: Secondary Revision and the Memory of the Vietnam War” History Workshop, no. 32 (1991): 134-150. http://www.jstor.org.libproxy.chapman.edu/stable/4289107.

[11] Berry Robison to wife, 22 May 1969, Robison Correspondence.

[12] “3rd Battalion, 187th Infantry Regiment ‘Iron Rakkasans,’” GlobalSecurity, accessed November 5, 2017, https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/agency/army/3-187in.htm.

[13] Robison to wife, 13 August 1968, Robison Correspondence.

[14] Robison to wife, 15 September 1968, Robison Correspondence.

[15] Robison to wife, 19 October 1968, Robison Correspondence.

[16] Spector, After Tet, xvi. President Johnson made a speech on March 31, 1968, conveying a change in policy concerning Vietnam—the move towards negotiations to end the war—and declaring that he would not run for reelection.

[17] For more information regarding the difference in perspective between the American public and the United States Military regarding the Tet Offensive, see Edwin E. Moïse, The Myths of Tet: The Most Misunderstood Event of the Vietnam War (Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 2017).

[18] Spector, After Tet, 25.

[19] Robison to wife, 14 October 1968, Robison Correspondence.

[20] Robison to wife, 14 October 1968, Robison Correspondence.

[21] Karl Marlantes discusses the rush some soldiers received in combat in his book What it is Like to Go to War, stating “When I returned from the war I would wake up at night trying to understand how I, this person who did want to be a good and decent person, and who really tried, could at the same time love an activity that hurt people so much.” From, Karl Marlantes, What it is Like to Go to War (New York: Grove Press, 2011), 68.

[22] Robison to wife, 8 November 1968, Robison Correspondence.

[23] Robison to wife, 14 May 1968, Robison Correspondence.

[24] Robison to wife, 21 June 1969, Robison Correspondence

[25] Bruce Russett’s “Doves, Hawks, and the U.S. Public Opinion,” outlines the debate surrounding being a Hawk or a Dove. Russett defines the two based on their views of world politics; hawks viewing a strong military to prevent war, and doves encouraging negotiation to accomplish the same goal. Russett notes, however, that “At their extremes, all these characterizations are caricatures. Each has a bit of the truth. States and individuals do compete, and cooperate.” From, Bruce Russett, “Doves, Hawks, and the U.S. Public Opinion” Political Science Quarterly 105, no. 4 (1990-1991): 516. doi:10.2307/2150933.

[26] Robison to wife 15 May 1969, Robison Correspondence.

[27] Richard Nixon: “Address to the Nation on Vietnam.,” May 14, 1969. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=2047.

[28] Robison to wife, 22 May 1969, Robison Correspondence.

[29] Robison to wife, 22 May 1969, Robison Correspondence.

[30] In discussing the origin of the “spat-upon Vietnam veteran,” Lembcke asserts that it was an attempt by the Nixon administration “to counter the credibility of the anti-war movement and prolong the war in Southeast Asia. Nixon had won election as a peace candidate, but he was also committed to not being the first American president to lose a war.” Thus, it is not unreasonable to find validity in Robison’s opinions concerning corrupt politicians. From, Jerry Lembcke, The Spitting Image: Myth, Memory, and the Legacy of Vietnam (New York: New York University Press, 1998), 94.

[31] Robison to wife, 22 May 1969, Robison Correspondence.

[32] For an in-depth assessment of Modernization Theory, see Michael E. Latham’s Modernization as Ideology: American Social Science and “Nation Building” in the Kennedy Era (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2000) and The Right Kind of Revolution: Modernization, Development, and U.S. Foreign Policy from the Cold War to Present (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2011).

[33] Robison to wife, 4 March 1969, Robison Correspondence.

[34] Kindsvatter, American Soldiers, 147.

[35] Jonathan Shay, Achilles in Vietnam: Combat Trauma and the Undoing of Character (New York: Scribner, 1994), 197.

Provenance: Submission

Cameron Carlomagno is a graduate student in the War and Society program, focusing on military and diplomatic history surrounding World War II and the Vietnam War. This research emerged from a graduate course at Chapman University on the soldier’s experience in war, and was presented at the Society of Military History in Louisville, Kentucky. She will be commencing research for her thesis concerning the role and memory of female spies in the Special Operations Executive.

Cameron Carlomagno is a graduate student in the War and Society program, focusing on military and diplomatic history surrounding World War II and the Vietnam War. This research emerged from a graduate course at Chapman University on the soldier’s experience in war, and was presented at the Society of Military History in Louisville, Kentucky. She will be commencing research for her thesis concerning the role and memory of female spies in the Special Operations Executive.

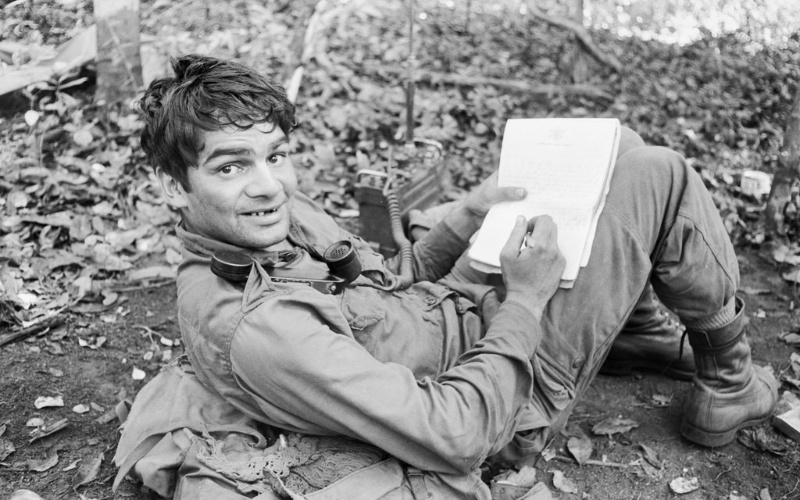

Featured Image: “Gunner Ernie Widders writes a letter from Vietnam” provided by Australian War Memorial collection is licensed under “no known copyright restrictions”

Bibliography

“3rd Battalion, 187th Infantry Regiment ‘Iron Rakkasans.’” GlobalSecurity. Accessed November 5, 2017. https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/agency/army/3-187in.htm.

Cortright, David. Soldiers in Revolt: GI Resistance During the Vietnam War. Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2005.

Eyerman, Ron, Todd Madigan, and Magnus Ring. “Cultural Trauma, Collective Memory and the Vietnam War.” Croatian Political Science Review 54, no. 1-2 (2017): 11-31.

Fussell, Paul. The Great War and Modern Memory. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1975.

Hanna, Martha. “War Letters: Communication between Front and Home Front.” 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War. Ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson. Issued by Freie Universität Berline, Berline 2014-10-08. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15463/ie1418.10362.

Hagopian, Patrick. “Oral Narratives: Secondary Revision and the Memory of the Vietnam War.” History Workshop, no. 32 (1991): 134-150. http://www.jstor.org.libproxy.chapman.edu/stable/4289107.

Hagopian, Patrick. The Vietnam War in American Memory: Veterans, Memorials, and the Politics of Healing. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2009.

Kindsvatter, Peter S. American Soldiers: Ground Combat in the World Wars, Korea, and Vietnam. Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 2003.

Lair, Meredith H. Armed with Abundance: Consumerism & Soldiering in the Vietnam War. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

Latham, Michael E. Modernization as Ideology: American Social Science and “Nation Building” in the Kennedy Era. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2000.

Latham, Michael E. The Right Kind of Revolution: Modernization, Development, and U.S. Foreign Policy from the Cold War to Present. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2011.

Lembcke, Jerry. The Spitting Image: Myth, Memory, and the Legacy of Vietnam. New York: New York University Press, 1998.

Marlantes, Karl. What it is Like to Go to War. New York: Grove Press, 2011.

Moïse, Edwin E. The Myths of Tet: The Most Misunderstood Event of the Vietnam War. Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 2017.

Oberdorfer, Don. Tet: The Turning Point in the Vietnam War. New York: Da Capo Press, 1971.

Richard Nixon: “Address to the Nation on Vietnam.,” May 14, 1969. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=2047.

[Robison (Berry) Vietnam War Correspondence, Box 1, Folder 13], Berry Robison Vietnam War correspondence (2015.064.w.r), Center for American War Letters Archives, Chapman University, CA.

“Robison (Berry) Vietnam War Correspondence.” Online Archive of California. Accessed December 1, 2017. http://www.oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8xg9wtn/admin/#aspace_519b0cfdf238d619e1cc23f8521d1575.

Russett, Bruce. “Doves, Hawks, and the U.S. Public Opinion.” Political Science Quarterly 105, no. 4 (1990-1991): 515-538. Doi:10.2307/2150933.

Schmitz, David F. The Tet Offensive: Politics, War and Public Opinion. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, INC., 2005.

Shay, Jonathan. Achilles in Vietnam: Combat Trauma and the Undoing of Character. New York: Scribner, 1994.

Spector, Ronald H. After Tet: The Bloodiest Year in Vietnam. New York: Vintage Books, 1993.

No Comments