Horse / Show

Shipping day

Faith is a problem horse. She kicks. She bites. She bucks. She grabs the bit and runs. None of this is her fault. Her last trainer punished her by whipping her into a gallop and forcing her to keep going until, exhausted, she had to slow. Every time she was mounted, Faith thought she was outrunning that whip. Inevitably, she became unrideable and unwanted until Jen, the owner and trainer at Four Willows Farm, took her in. For two years, Jen has been bringing Faith back to herself, and the mare is finally ready for an amateur rider. At the Heartland Classic Fall Spooktacular Horse Show, I’ll be the one in the stirrups.

This is my first season back on the show circuit. As a kid, I started showing at age seven, had my own gelding by age eight. Horse-crazy and spoiled, I spent whole weekends at the barn, sleeping in my trainer’s spare room and rising for morning trail rides before the work began. I owned a horse who turned heads, with a name that trainers still remember. My pictures appeared in glossy magazines. I entered the most competitive shows in the country—Rock Creek, Lexington, Louisville, my summers chock-full of trips to show grounds all over the country.

This is my first season back on the show circuit. As a kid, I started showing at age seven, had my own gelding by age eight. Horse-crazy and spoiled, I spent whole weekends at the barn, sleeping in my trainer’s spare room and rising for morning trail rides before the work began. I owned a horse who turned heads, with a name that trainers still remember. My pictures appeared in glossy magazines. I entered the most competitive shows in the country—Rock Creek, Lexington, Louisville, my summers chock-full of trips to show grounds all over the country.

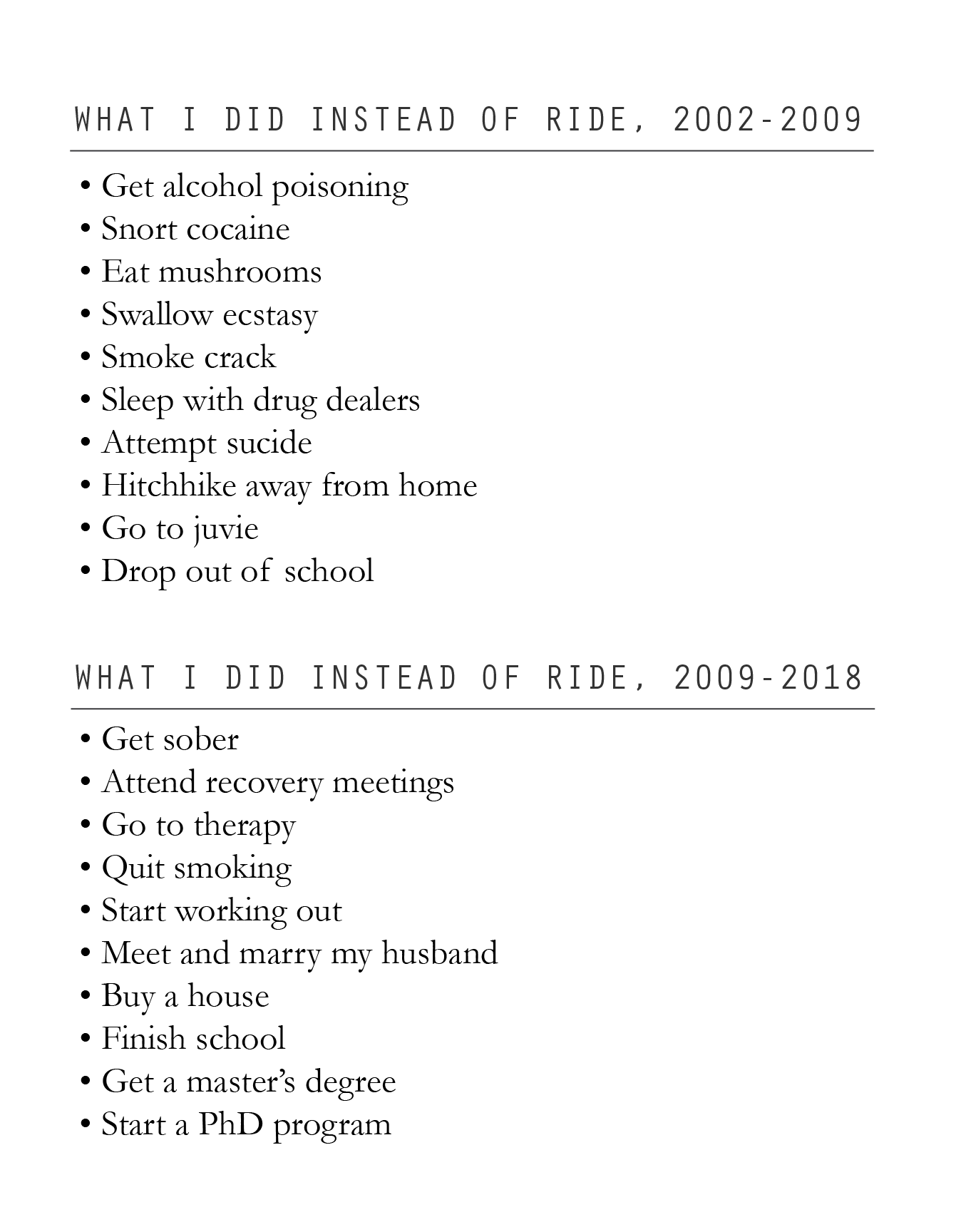

By the time I could legally drive, I had been seduced by boys, booze, and drugs instead of Saddlebreds. Partying turned to habit turned to need, and I lost a decade of my life to addiction and depression. It’s been twenty years since I started drinking and ten since I got sober. Last year, I started jonesing for horse—the equine, not the heroin kind—and I found Four Willows. When money got too tight for lessons, Jen let me start working for trade.

I text Jen while they’re on the road from home in Greenwood, Indiana to the showgrounds in Springfield, Ohio. She assures me all is well. No flat tires, no fights. Once, Faith got in a fight with her neighbor mid-ship. She bared her teeth and reached over the divider, taking another mare’s neck in her teeth, and clamped. We had to pull into a Taco Bell to break the girls up and calm them down. But nothing happens today. Just smooth highway driving, the three horses quiet on the padded rubber mats, ankle-deep in sawdust, chewing hay, watching the traffic pass as they zip over blacktop while standing perfectly still. Three thousand pounds of muscle, three hearts as big as human heads. My heart is already at the showgrounds, already with Faith.

Four women are working this show. Jen is short and quiet, with strong forearms, a blonde-on-top two-tone bob, and a penchant for Scentsy candles. Around her neck, a silver cross. Linda, slender and soft-voiced, is her mom. She can work a show in a cream bell-sleeved sweater without getting it dirty. Then there’s me. Unbrushed hair. Wrinkled shirt. Tattooed shoulders. Gauged ears.

Four Willows Farm is a small family business. Nineteen stalls, thirteen acres of pasture, an indoor arena. The specialty is Saddlebreds, a fancy

breed—long-necked, powerful, and made for the show ring. They’re usually shown saddle seat, a little-known riding discipline that rabbit-holes into a world of its own. Don’t bother Googling it. Most barns barely have a webpage. This industry runs on reputation and word of mouth, not Twitter. Four Willows isn’t one of those big Saddlebred outlets with air-conditioned stalls, a marble-topped bar in the viewing room, and an automatic watering system. Those barns might haul eighteen horses to a show with an army of grooms in tow—mostly Latino men, many undocumented—to muck stalls, clean tack, and towel down sweaty horses.

Jen and her parents run the barn by themselves, with a couple of teenagers to help on afternoons and weekends. It’s a 365-day-a-year job, and they’ve been doing it for eighteen years. Horses must be worked, fed, and turned out, even on Thanksgiving. Saddlebreds are elite athletes. They cross-train. They wear custom shoes. They get chiropractic adjustments, take vitamins, eat performance-quality grain. Only in winter, after show season is over, do we turn them loose to buck and kick up dust—to act like horses, not Russian gymnasts prepping for the Olympics. Not all barns do this. Some keep them show-shod year-round.

While I’m sitting in my 19th-century American Literature class, I check the time. Jen and company should be in Springfield. I know exactly what will happen next. First, the horses will be led in. They’ll drop to their knees in their stalls to roll, gleeful, in their new beds. They’ll crane their necks over the bars, flattening their ears and baring their teeth at their new neighbors. Their travel blankets will have to come off so their monogrammed, satiny show sheets can go on. Once the horses are settled, Jen will light a cigarette and head to the office to check in, to make sure all the entries are tallied and in the system.

Day One

I arrive in time to clean stalls. With plastic-tined pitchforks, the horses stepping around us, we scoop piss-soaked shavings and piles of shit into a big bucket. I don’t mind the tang in the air. While I muck, I can feel the heat of Faith’s body radiating, smell its furry musk. When she notices me, nuzzles me, my heart drops to the bottom of my chest and throbs, warm and dumb. Ricky just wants to play. He nibbles my ponytail, the pitchfork handle. He swishes his tail against the stall wall. He dunks his feed-bin in his water bucket. He reaches his head over the stall and snags a wrap from someone else’s jog-cart, places it in his stall as if it were a prize.

Ricky is Linda’s horse. He’s a liver-chestnut gelding with a flowing mane and thick tail. His registered name is Who’s Lookin’. All American Saddlebreds have a show name and, because the show names are too ridiculous and long to say on a daily basis, they have a barn name, too. Often, the two have nothing to do with each other. Linda and Ricky show today in the 1:00 session, the Show Pleasure Novice Horse class. Each session at a horse show is divided into classes, and each class is for a different division, a different type of horse or rider. The Spooktacular boasts 151 classes over three days. It’s dizzying.

To prepare Ricky, we unbraid and wash his tail, blow-drying it and spritzing it with leave-in conditioner. We sand the surface of his hooves and paint them with shoe polish. Jen braids a maroon ribbon into his mane. I hold him, the lead rope loose, while he stands for his grooming. He stretches his whiskery lips towards my hands and butts me with his forehead.

To prepare Ricky, we unbraid and wash his tail, blow-drying it and spritzing it with leave-in conditioner. We sand the surface of his hooves and paint them with shoe polish. Jen braids a maroon ribbon into his mane. I hold him, the lead rope loose, while he stands for his grooming. He stretches his whiskery lips towards my hands and butts me with his forehead.

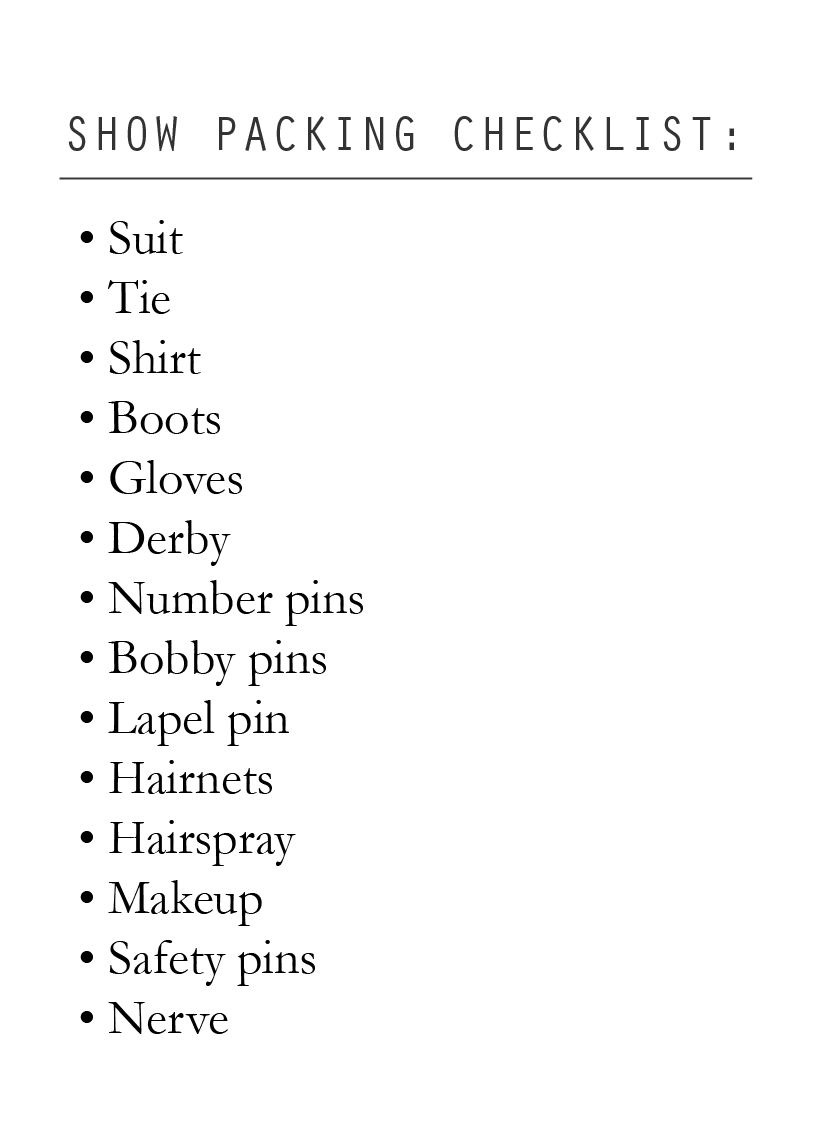

Meanwhile, Linda is smoothing her hair into a tight bun at the nape of her neck. She’s gliding on eyeliner, shadow, and lipstick. She’s pulling on tailored and flared wool pants, a button-up shirt, a white vest, a tie, and a shimmery blue knee-length suit jacket. While we wait for her class, we chat. When she laughs, it’s high and tight. I can tell she’s nervous.

When the announcer finally calls Linda’s class, she and Ricky trot in from the warm-up ring. Organ music pumps in time with the horses’ movements. It’s played by an old lady with glasses and set hair, possibly the same one who played for me fifteen years earlier. There are six entries, and, as the big-voiced announcer calls it, they trot, walk, then canter around the ring. Stop, turn, reverse, repeat. In the center, the judge’s stand—a fenced-in rectangle holding the organist, announcer, awards, and photographer’s equipment. The photographer walks from one end of the stand to the other, squatting to snap photos, rushing to adjust her lens before the next horse shoots down the rail. The judge himself, suited and tied, stands in the middle with his clipboard, turning and turning to watch these horses go. The bigger shows have multiple judges, the World’s Championship up to five, but here, there is only one.

Ricky doesn’t win. He’s big and gorgeous, but he’s new to the barn, and he and Linda are still finding their rhythm. If the judge scored on handsomeness alone, he’d win, but first place goes to the showiest horse, the one with the biggest trot, the most motion, and the nicest headset. This is an area where money goes a long way. With enough cash, you can buy a winning horse pre-made. Ricky’s a good horse with potential, but he’s still got some kinks to work out. He didn’t place well, but he showed a clean class, and Linda is happy with that.

After the session, I groom Faith for our practice ride. She loves the currycomb, stretching her neck up and wiggling her top lip while I massage her skin in small circles. But when the brush comes out, the ears go flat. She glares and bites the air. She kicks, and I have to watch her body closely to make sure those legs don’t piston my shin. But when I brush her face, she drops her head and closes her eyes so I can brush the dust from the star on her forehead.

The show ring is empty except for a tween trotting on a big gelding with a white blaze on his face, her trainer yelling at her from the middle. “Open and close, Amy! Open and close. That’s right. Yeah boy!” “Yeah boy!” is the traditional Saddlebred call of praise. It’s yelled short and quick. At shows, you can hear it shouted from the rail during exciting classes. You’ll also hear “yew!”, “woo!”, and “yip!” but none of those mean as much as a “yeah boy!” When the crowd cheers, the horses perk up. They step higher and brighten. They prick their ears. Their whole bodies bloom.

We warm Faith up in stretchies, a tube cuffed between her front legs—like a dancer warming up her shoulders with resistance-band butterflies. They make Faith’s legs pop, make her march. As soon as they’re on, she’s rolling. This mare wants to go. The world sharpens around me, snaps into place. It’s all I can do to slow my post and keep her from breaking. There’s no time to think. If I think, I’ll end up in the dirt. Faith is huffing like a freight train, moving fast and punchy, and yeah boy, it’s some kind of high. My fingers tingle. I get lit when I ride.

Jen calls from the rail, “That’s it. That’s it. Right there. Little bit of curb—tip her nose in. Good.” Faith is so pumped. Stepping so high, she breaks the stretchies. Around the ring, people are watching. I bring Faith to a walk and reach up to pat her neck. Then, we canter, and, thanks to all that is holy, thanks to hay and grass and horse-breath, Faith stays slow. We’ve been kicked out of a class for cantering too fast, so I hold my breath every time I angle to the rail and give her the cue. As we take off, I’m sliding my ass in the saddle and pushing my legs out and away, bumping up with my pinkies, feeling Faith’s body under me, her mouth tethered to me through metal and leather. This is how we talk, and she’s listening.

After our ride, back in the stall, I give her a mint. She licks my hand and lowers her head so I can towel the sweat from around her ears. Faith is always in a good mood after she works. These are my favorite times with her. The post-ride buzz. I lean into her and scratch her neck. She head-butts me, noses my pockets, lips my jacket, grabs its zipper between her teeth.

While she dries, Jen and I wash Faith’s tail and do her feet. Saddlebreds receive more pedicures in a show season than I will in a lifetime. As we work, Jen tells me about the early days of working with Faith.

“We tried everything. Putting a western saddle on her, hanging sandbags from it to get her used to the weight. When I found out she’d stop kicking and bucking if someone cracked a whip—not touching her with it, just making noise—I knew I’d figured her out. She needed that encouragement to move forward.” That wasn’t long ago.

This tiny woman accomplished what a man couldn’t—wouldn’t—do. I ask Jen why most of the trainers are male. She doesn’t know, but no one supported her decision to become one. “One trainer talked down to me. It only takes ten seconds to run in there and pin on that blue ribbon. It’s a lot of work to get to that point.” She snorts. “As if I’m in this for the ribbons.”

I’m proud to be part of a woman-owned, woman-run barn. I look into Faith’s round, wide eyes. “It’s definitely not about the ribbons.”

Day Two

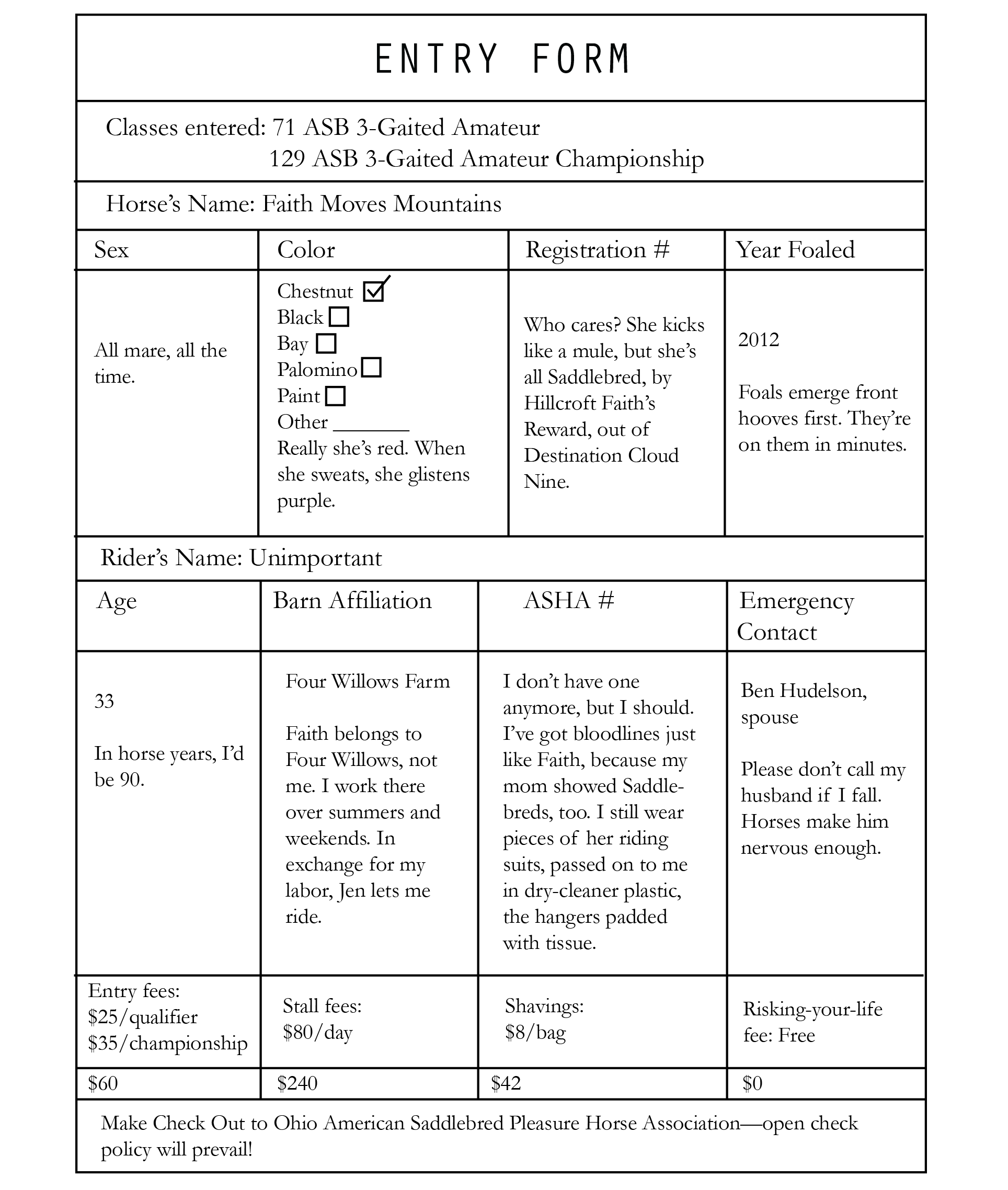

When I shuffle into the showgrounds, rubbing crust from my tired eyes, Faith is dozing on her feet, one back leg cocked, neck low, eyelids lowered. After the morning feeding and cleaning routine, I hairspray my frizz into a bun, layer on make-up, pin my number to my teal coat, and stick a horseshoe brooch to its lapel. My suit is old. I wore it when I was last showing, when I was a teenager, and it barely fits. The sleeves are too short, the shirt’s collar chokes, and the coat is fraying at the hem, the lining falling out. It doesn’t matter. All eyes will be on Faith, not me. She’s the one who needs to shine.

We take Faith outside to warm up, and the wind whips the tail we so carefully combed and set. Faith’s nostrils are dilated bigger than eggs. She spooks at the trash bags snapping in the air. She spooks at the F150’s parked outside. She spooks at the fence post. After a few trips around the outdoor ring, we head inside to wait for the announcer’s call. Linda polishes my boots while we stand. Jen watches the other horses, hands on hips, her face flat. It’s impossible to tell what she’s thinking. Jen’s words of praise are sparse. A quick, “Good job today,” while I’m walking out the barn door is enough to make me grin the whole way home.

The warm-up ring is always chaos. Horses—some hitched to a cart, some under saddle, some ridden by trainers, some under kids—all zoom around in different

directions. Collisions aren’t uncommon. It’s no wonder we have to sign a waiver. Finally, the announcer calls it. “Class 71, Three-Gaited Amateur, the gate is open!” The Three-Gaited division is one of the most thrilling in Saddle Seat. The horses have to be powerful yet elegant, with strapping trots and perfect headsets. To show off their long necks, they’re shown with shaved manes. Faith sets her head like a chess piece. She looks great in her buzz-cut. Jen turns. “You ready to kick some ass?” I nod and get to it. But I must have stiffened, because Faith loses some of her punch, and, until we reverse, I can’t get it back. The judge pins us third out of three, but I’m proud of Faith. She did well. She didn’t kick. Didn’t buck or rear. Didn’t break.

I change out of my show clothes, sling a towel over my shoulder, and walk Faith up and down the aisles, her hooves clapping the concrete. She likes to stop, to look. And I let her, stroking her shoulder, her neck, before drying off her sweaty flanks. I give her an apple. She chomps it, her eyes widening, her head nodding “yes!” just before she bites me, bruising my arm. I sigh. I love her.

That night, Jen and Junior—registered name Rhythm’s Revival—suit up for their turn in the ring. Five-Gaited Ladies. By now, the routine is pat. Wash and dry tail. Polish hooves. Braid ribbon into mane. Brush. Tack. Warm up. Show. Junior is a moose in a horse’s body. His head is as long as my torso. Even with a stepstool, Jen can barely mount him, especially when he’s stimulated by all the excitement of the show.

That night, Jen and Junior—registered name Rhythm’s Revival—suit up for their turn in the ring. Five-Gaited Ladies. By now, the routine is pat. Wash and dry tail. Polish hooves. Braid ribbon into mane. Brush. Tack. Warm up. Show. Junior is a moose in a horse’s body. His head is as long as my torso. Even with a stepstool, Jen can barely mount him, especially when he’s stimulated by all the excitement of the show.

Once she’s up, Junior zips around the other horses, strong enough that Jen can barely stick in the saddle. I’m jealous. I want to be mounted on all that power. When Jen brings Junior into his rack, he’s got the attention of the whole warm-up ring. He’s flying, stepping high, his shoulders rippling, his black mane a flag. I’m grinning, catching a contact high from her ride.

In the ring, Junior nearly sets off sparks in the packed-dirt footing. The organ plays “The Phantom of the Opera.” The crowd starts cheering for their favorites, yelling and banging on the rail. Lots of “yeah boy’s” and “yeeewwws.” Junior’s speed means he gets more attention than anyone, but he breaks his rack for a few beats right in front of the judge, so he comes in second. The crowd breathes an audible “Noooo.” They’re disappointed. They wanted the big moose to win.

People compliment Junior all night. It’s fun to be linked to a legend. After the evening usual—cool out Junior, water, feed, sweep the aisle—we eat bad concession stand food, thankful anything is still open at ten. I love the buzz of conversation around me. “I heard Eliza moved to Arizona and took her walk-trot horse with her.” “Whose pony was that who cut Dana off?” “Jen, we like your gaited horse. Love the way he thinks.” By now, people are drinking, but I’m drunk enough on horse that, even if I still drank, I wouldn’t need anything stronger than water.

Championships

By the third day, even with just three horses, we’re tired. The hours have blurred into rote mode, a circle of haying, waiting, walking, and haying:

7:00: hay, grain, water

8:00: clean stalls

9:00: prep horses for show

10:00: watch some classes, try to out-judge the judge

11:00: check out the vendors again to see if they have brown show gloves (nope)

11:15: watch Jen smoke a cigarette, then another

11:37: flip through Saddle Horse Report

12:05: groom and tack

12:37: warm up

12:43: wait

12:45: wait

12:46: show

12:52: walk back to barn, dismount, cool horse out

2:00: hay, grain, water

Linda and Ricky show in their championship and have another strong ride but don’t make the cut into the top three. Watching her cool him out after, you’d never know they didn’t win. She slips him mints and walks him, telling him how good he is, her eyes soft and affectionate. After she braids his tail, she wags a finger in his face. “Don’t go dipping your tail in your water bucket again, you hear me?” Ricky looks at her sidelong, and she shakes her head. She knows his tail will be dunked as soon as she turns him loose.

Faith and I are next. We warm up inside, and she’s shaking her head as we walk, telling me she wants to groove. I soften, and off we trot, her neck jacked back in my lap, her knees bursting up. I’m holding all her energy at a brink, a water glass that would spill with one more drop. But we don’t spill. We stride, and off we go into the arena, the organist skipping over a syncopated “On Broadway.” We’re competing against the same two horses as before, and this time, I’m out to beat the bay. Faith has a nicer headset. She could totally take him.

I make pass after pass, but I can’t catch the judge’s attention. Every time I approach, he turns away. I know I’ve lost the class. The photographer likes us, though. I see her flash from the corner of my eye each time we pass.

When the announcer calls for the gaited championship, Jen and Junior charge in, and the crowd whoops. They remember their moose. I’m banging on the rail and “yeah boy”-ing along with the audience. Suddenly, I hear a trainer next to me yell for Jen. “You lost a shoe, Jennifer! Stop.” Jen pulls Junior to a halt and walks into the middle. Now that he’s slowed, I can see that he’s barefoot on his left front. His shoe had popped off, taking a chunk of his hoof with it. The farrier has to reshoe Junior in the middle of the class, and he works fast, pounding the nails in while I try to keep the moose still. In minutes, they’re working on the rail again. Junior could have won it, but he got so pumped from his unscheduled mid-class break that he lost his rack, making the crowd groan collectively again.

When it’s over, I meet Jen at the gate. “Good job,” I tell her, walking next to her as we clop back to the barn. She smiles. “You and Faith did good, too. So much of the judging is political, you know.” I smile. I know. It’s nice to be with a barn that cares more about horses than ribbons. Other barns wouldn’t rehab a blind horse. Or keep one who broke his leg and couldn’t be ridden anymore. Or rescue a starving old gelding from a field. Or take in Faith.

Four Willows doesn’t sponsor exhibitor parties or hold box seats at the Saddle Seat World’s Championship. They don’t buy sections in Saddle and Bridle to feature their riders. They do honest work, and they work hard, every blue ribbon earned, not bought. As for me, no one knows who I am anymore. I’m a newbie back on the Saddlebred scene, and I haven’t taken a victory pass all season.

Through all the years of not-riding, I’d carried an old photo of my childhood horse in my wallet, and even though I’d left credit cards in bars, let wads of cash go missing, and even misplaced my car, I never lost that picture. Clearly, no matter how mind-muddled I was, how drunk, I’d missed riding.

Sure, winning would be nice, but I’m happy just to be here, smelling horse.

Tear-down

Within an hour, we’ve packed our trunks. Jen’s dad rumbles in with the dually to hitch the trailer and pull it around. The fall air is chilly, and I zip up my hoodie before I sling a tailset over my shoulder and head towards the six-horse. Packing the storage compartment of the trailer is careful geometry. A game of Tetris with saddles and eighty-pound trunks. Jen chuckles. “It’s like moving, but we do it twelve times a year.”

Before we leave, Linda brings us lunch—chicken tenders for her, taco salad for Jen, a plate of French fries for me. It’s no wonder we call her Mama Linda. Show sheets come off the horses and are replaced with their rough shipping blankets. Faith paws when she sees me coming with hers, gnashing, pinning her ears, and rolling her eyes. She acts wild, but I know she’ll let me slip the plaid over her head. She knows I’ll scratch her withers after I buckle the belly-straps.

The showgrounds are filled with idling Chevys and semis, trailers open, ramps down. All the barns around us are loading up, tired-giddy, friendly and laughing as they walk back and forth to their trailers with trunks, saddles, chairs, and bags of dirty towels. They call to Jen. “That gaited horse of yours! Whew! Wish I had a horse who could speed-rack like that.” She smiles, glowing, and thanks them.

Finally, one by one, we lead the horses to our own trailer, walk them in. We tie in their hay bags and they munch, looking bored. When they’re in, we take our places. Linda’s car first, then the truck and trailer, then me in my Jetta. As we leave the grounds, I flip on the radio, then turn it back off, preferring the quiet hum of the road.

Our caravan pulls onto I-70 and I say goodbye to Springfield, Ohio. My hair is still helmet-hard with hairspray. My pants smell like horse piss. My boots are caked with dirt, and thanks to the cracks in the leather, some has sifted through to my socks and gritted up my toes. I haven’t slept well or eaten well in days. I’m surprised to feel tears behind my eyes, but I shouldn’t be. This is the end of my first show season back, and the whole thing has felt like coming home.

From behind, I can’t see Faith, but I know she’s there, breathing, shifting her great weight from side to side. If I could buy her, I would, but I can’t. I have to settle for being part of her puzzle, a human who gives her kindness instead of kicks even when she kicks at me. If I’m lucky, I’ll get to show her again. I’m already planning for it, thinking about how to afford a new coat, wondering what color might look best with her red.

When Faith and the boys get back to the barn, the horses who didn’t travel will whinny to greet them. Jen and Linda will lead them slowly off the trailer, careful on the ramp, making sure they don’t fall. They’ll return to their home stalls, crane their necks over the walls to greet their neighbors. They’ll sleep well tonight, tired from the trip, from three days in an unfamiliar barn. I will, too.

I press the accelerator, pull my car up next to the trailer, look right. Through its window, I catch a glimpse of red velvet, a perked set of ears, and one liquid eye meeting mine.

Notes

- Oser, Christine. “Secretariat’s Heart Size: Inside the Tremendous Machine.” Horse Racing Nation, June 16, 2017. https://www.horseracingnation.com/news/The_Tremen

dous_Size_of_Secretariat_s_Heart_123#.

- Kentucky Equine Research Staff. “From the Heart.” Kentucky Equine Research, December 28, 2017. https://ker.com/equinews/from-the-heart/.

- Pascoe, Elaine. “How Horses Sleep.” Practical Horseman Magazine, March 12, 2002. https://practicalhorsemanmag.com/health-archive/eqzzz629-11363.

- “Natural and Artificial Gaits of the Horse.” My Horse University. My Horse University Online Horse Management, April 23, 2018. https://www.myhorseuniversity.com/single-post/2017/09/25/Natural-and-Artificial-Gaits-of-the-Horse.

- Eastman, Tim G. “Fractures in Horses: The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly.” Steinbeck Country Equine Clinic, August 15, 2014. http://steinbeckequine.com/article/fractures-in-horses-the-good-the-bad-and-the-ugly/.

- Huntington, Peter. “Recent Colic Research Update.” Kentucky Equine Research, January 14, 2018. https://ker.com/equinews/recent-colic-research-update/.

Author Biography

Emma Faesi Hudelson is a teaching fellow and PhD candidate studying literary nonfiction at the University of Cincinnati. She lives with two dogs, two cats, and one husband in a house by the woods near Indiana’s White River. Her work appears or is forthcoming in BUST, the Chattahoochee Review, The Fix, The Rumpus, and other publications. Her essays have been selected as finalists in the 2017 International Literary Awards and Creative Nonfiction’s Spring 2018 Contest.

Visual Artist Biography

Chrissy Allen studied at Lewis and Clark University. When she isn’t photographing horses, she’s riding them. You can follow her on Instagram at @_raisingthebar_.

No Comments