The Journey into Terror

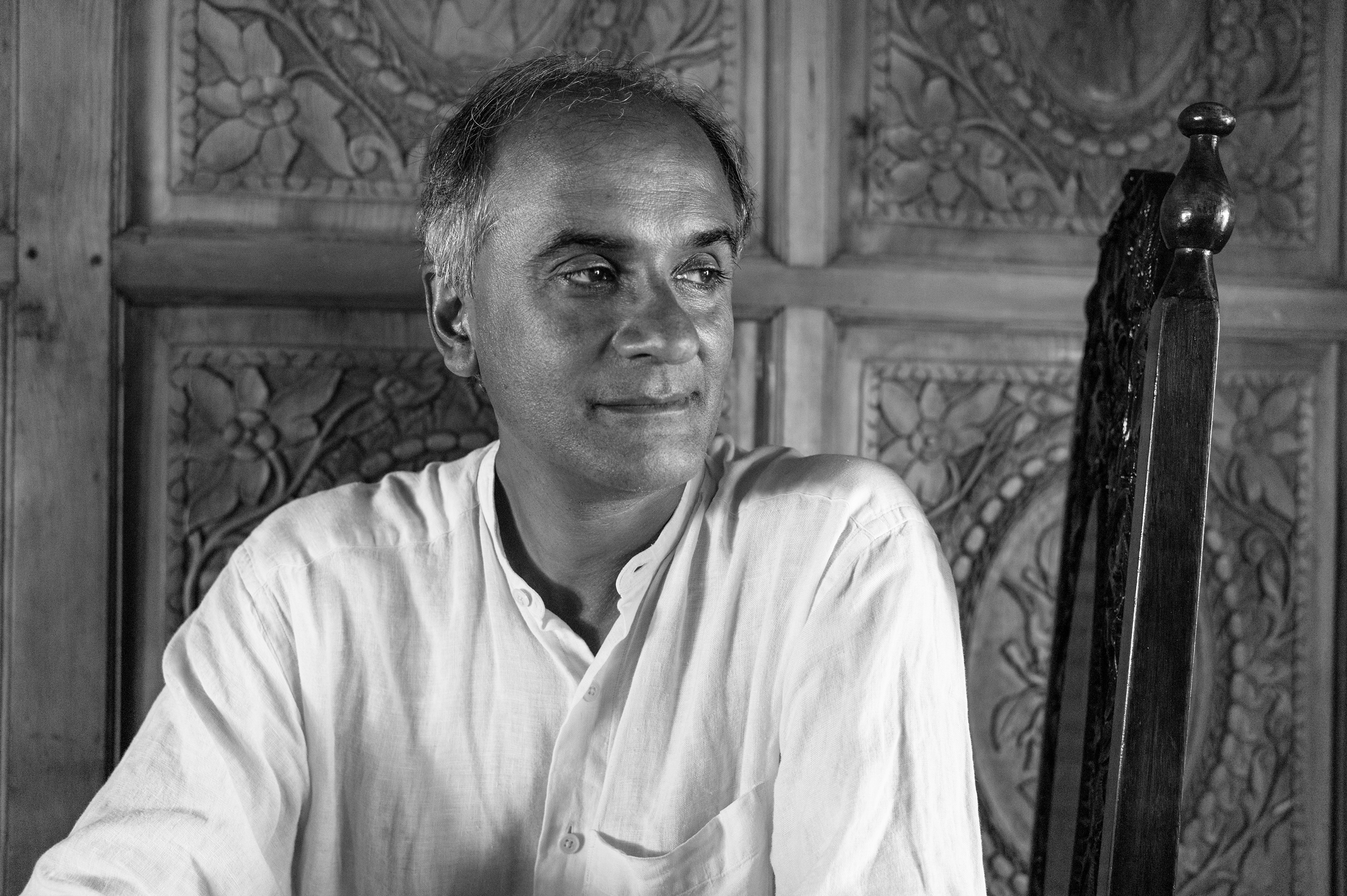

Pico Iyer

I stepped out of the unsteady Yemenia jet and looked around me. Within seconds, I understood why a seasoned war photographer had refused to “risk his life” by accompanying me to Aden, the historic port in southern Yemen. After forty years of constant warfare—the Brits, the Soviets, unending battles against forces from North Yemen—the city around me was the most blasted place I’d ever seen. Old women were foraging along the potholed streets, and every sign of civilization, as we think of it—schools, hospitals, homes—had been reduced to rubble. Just to enter the lobby of my hotel—right next to the place where terrorists had recently blown up the U.S.S. Cole—I had to walk through a security machine, as at an airport; and every time I stepped onto the beach the hotel commanded, it was to find the whole stretch of sand entirely empty, save for three armed soldiers on one side of me, and three armed soldiers on the other.

Osama bin Laden’s ancestral village lay not many miles away, and my seasoned travel-agent, who’d grown up in Berlin as bombs fell every hour in the 1940s, had been reluctant even to issue a ticket to Aden. Every Yemeni man carries, by custom, a dagger and the main source of revenue in the country’s villages, dominated by tower-houses that look like fortresses, is still the kidnapping of outsiders. And I, implausibly, was wandering alone around this wasteland, having been invited by an editor in Hong Kong to write a breezy story retracing the footsteps of Zhang He, the 15th century Muslim eunuch admiral who had led his long “treasure ships” on seven celebrated journeys from China as far as the Perfume Coast of Yemen and Oman.

I’d often told friends that one point of travel was to journey into—and so through—the needless apprehensions that keep us from the world. So many things are terrifying when you see them in your mind; actually go through them, and you barely have time to be alarmed. My home in California had burned down in a forest fire once, and I had been stuck inside the conflagration for three hours, surrounded by 70-foot flames whipped on by sundowner winds at Ferrari speeds.

What is horrifying to hear about, or contemplate, was simply a fact of life as I sat there, foolishly taking shelter inside a car, trying to ensure my mother’s aging tabby cat didn’t expire, and listening to an opera on the car radio rather than dwelling hopelessly on how perilous our situation was.

In Yemen, though, I soon realized I was alone and even farther from help than in any forest fire. No one knew where I was, and the fact that I looked like a local—a protection, I’d thought—implicated me in every single transaction. There was little to do or see in Aden, and when once a beseeching local came up and offered to show me around, the only place he could think of worth visiting was the cemetery. We spent a long, hot afternoon inspecting the graves of nuns, of missionaries, of everyone in my new friend’s family; anyone who had tried to be of help in Yemen lay deep underground, it seemed.

There is much, much more I could tell you about my stay in the land of permanent revolution; my flight out was canceled, I had to drive across country, through the villages of tribal kidnappers, at dead of night, I found myself often in empty streets filled with nothing but oil drums and over-excited teenagers waving AK-47s. But for now, perhaps I’ll alight on just two of the things I brought back from my trip.

Five weeks after I returned to Santa Barbara, the last word in seeming protectedness—the town where my mother lives looks like a gated community of sub-tropical affluence and ease (until forest fires roar down from the hills)—my mother hurried into the room where I was writing to say that Yemen, the place I’d just returned from, was all over the TV set: men were flying planes into the World Trade Center, she said, and suddenly the poorest country in the Arabian Peninsula was seen as an epicenter of evil, a symbol of everything we should be pledged to destroy. Simply by stumbling through the unknown, I came to find, I was hearing the news differently than my friends all around me in California did. They hadn’t had the chance to meet the kids playing in the Aden street, the old woman banging on the window of my taxi, the sad-eyed man who led me through the graveyard.

But I also registered something closer to home as I looked down at what I was writing.

Wasn’t this what every writer sensed, deep down? That the point of our calling was to go to all the places within we’d otherwise avoid? That the grace of a writer’s life is that she is invited—expected even—to say the things she’d otherwise be embarrassed to say, to return to the moments she’d generally be happy to brush aside, to look head-on at the terrors that most of us deny for our own peace of mind?

It may sound strange to those of us who travel mostly on the page, but in some ways my trip to Yemen became a metaphor that I always carry with me for what I do at my desk every day.

I accept an assignment on a lark, and it sounds like an exotic adventure. The more fully I travel into it, the more I realize I’m getting in deeper than I know—or want. But there’s no way out. And when life throws a shock at me—as it will—and suddenly turns everything I thought I knew upside-down, the one thing for which I’m grateful is that writing allows me–in fact compels me–to go exactly where I’d never go in my right mind. By taking me into the depths of everything I fear—the Yemen of the soul—it shows me that most of my fears are inside me, and the world is impossible to anticipate. There’s no virtue in seeking out terror, I tell myself—yet my every close encounter with it has left me stronger, and more wide-awake than I would ever be without it.

Provenance: Invited submission.

Pico Iyer is an essayist and novelist who lives the majority of the year in Japan. Some of his books include Video Night in Kathmandu, The Lady and the Monk and The Global Soul. He is an essayist for Time and also publishes in Harper’s, The New York Review of Books, and The New York Times.

Pico Iyer is an essayist and novelist who lives the majority of the year in Japan. Some of his books include Video Night in Kathmandu, The Lady and the Monk and The Global Soul. He is an essayist for Time and also publishes in Harper’s, The New York Review of Books, and The New York Times.

“A structural building and pier of the city of Aden.” by T3n60 is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

No Comments