The Hating Cells

Liz Fyne

“Derek, show me the cells.”

I retrieved them from the incubator, carried the plastic cell culture dish with pink liquid media to the microscope.

They were hating cells. We didn’t mean to make hating cells. The goal was to make loving cells.

Paul leaned forward, adjusting the focus to the bottom of the dish where the cells grew. A song played in the background, music from the lab radio perched in the corner by the rusty CO2 tanks. It was a woman’s voice, deep and bluesy, singing in agony of romantic abandonment.

Paul stood straight, still facing the microscope but staring across the room at nothing. So many years we’d been trying, and now it was the wrong emotion.

“Should I kill them?” I asked.

“No, keep them growing.”

***

We started the love cell experiments, initially, with heart cells—freshly harvested from the corpse of a young woman who’d died while still much smitten with her fiancé. We’d captured his own lovelorn tears, adjusted the pH and sterile filtered them, then added them to the culture media bathing her purified cardiac remains.

But the cells withered and died while distributed sparsely along the bottom of the dish, unable to take comfort in each other’s companionship and her lover’s liquid last adieus.

“They felt too alone,” said Paul. “Did you add the oxytocin?”

Oxytocin otherwise known as the love hormone.

“I did.”

“Next time add more. They have to love each other to survive.”

Later that day I stood in the lab, looking at the Western blot we’d done to confirm oxytocin receptor expression on the dead woman’s cardiomyocytes. The oxytocin, itself, we’d purified fresh from a different woman, during labor, flush with the ardor of new-mother crazy wild child love.

“Maybe we should use a man’s heart,” I said. “Maybe it will respond better to the labor oxytocin.”

Paul didn’t know; I didn’t know. It was guessing in the dark. And what heart we’d get next time—whose body would perish filled with longing and passion soon to expire—we couldn’t know that, either.

But if this could work, if we could make cells that loved and then extract from them the essence of all you needed, the power of, what I will always do—

But the experimental and theoretical logistics were daunting; the raw materials were hard to acquire. Months and years passed us by: Paul and I in the cell culture room with the filthy floor, the smell of ethanol on our hands, rank swill of bleached blood in the sink.

Natalie Cole on the iPod. This will be an everlasting—

In my mind’s eye I saw her with a fantastic round afro, dancing onstage in a long blue dress. Maybe we needed a singer’s heart, I thought, an artist, the incurable romantic who died trying to master the Petrarchan sonnet.

Because no matter what we did the cardiac tissues of freshly dead lovers rounded up and peeled from the bottom of the dish. Lifeless floaters in a pink media sea.

Paul stood leaning with his back against the workbench. He was gaunt with frustration, restless with desperation.

“They have no soul,” he said.

“They were all bleeding love when we took them.”

“They had passion but no thought. No capacity to grasp the greater universe.”

Even a cell, tiny chemical factory and the smallest living unit, should possess within its core some element of sentient awareness, some essential, infinitesimal frisson—touch it and within the bounds of its tiny microverse the cell recoils or embraces. It is alive, it senses, it loves at the most basic level—love of itself.

Take cells that are not just loving but mad with love, drunk on endorphins and rush of adoration. Maybe those cells can be coaxed, by administration of the appropriate external stimuli, to experience something more profound than selfish love—in fact to find love of each other. This new kind of other love would be tendered from one cell to the next in the form of a yet-undiscovered signal. It was undiscovered because it wasn’t just a chemical but a blossoming of chi. Paul believed that this metaphysical bloom could be located, extracted and purified through the application of standard and non-standard scientific techniques. Then administered to intoxicating effect. Cure war and greed. Anger and hate.

At least that was the idea. Our colleagues at the university found it far-fetched but I found it irresistible.

“Heart cells won’t do,” said Paul. He caught me in his long hang-dog stare. “We need heart cells plus brain cells.”

“You can’t co-culture cardiac cells and neurons,” I said.

“You can. There’s a lab that did it using micro-fabrication techniques.” He paused. “Heart cells have love, but brain cells have soul.”

“We can’t purify the soul.”

“We can use it in co-culture.”

Paul wanted more than crude organic molecules like oxytocin—he wanted the real thing. And so did I. I wanted to so much it made me cry, at night, when I lay alone in bed after another eighteen-hour day striving for perfection.

So we did our best to capture the soul, buried within the gore of fresh tissue. We used cells from the brain’s limbic system, seat of emotion, feeling for everything.

Paul stood behind my chair in the cell culture room and watched me; his eyes were red with sorrow, joy. A tangle of feelings that grew within him every time he considered the possibility of actual success.

Rock the cells on the rocking platform—memory of life in-utero. The mother said that all during her pregnancy she rocked in a chair by the window, her belly warm from a big orange cat. We got her tears also; shed when the doctor pulled the plug.

“Use everything well,” she said. She sat on a hard plastic bench, pale and shaking. “Do something good from all the evil in the world.”

Her daughter died in a robbery gone bad. Drug addicts desperate for a hit.

More love, that’s what Paul would say, and fewer people will turn to the artificial high of drugs.

Because she was alone we took her for coffee, so she didn’t have to leave the hospital by herself, anonymous in the back seat of a cab. Paul spent the night on her sofa. I came the next morning at ten and when he opened the door he looked as if it was his own daughter who’d died.

“Paul,” I said, “don’t let this project kill you.”

I worried about him, sometimes. I worried about myself, too, but Paul more so. Like him I was alone and driven but I was younger. If the project failed, I would move on. It would be hard, but I would. But Paul?

“She lost everything,” said Paul.

“She will survive.”

“How can life be so cruel?”

“I need you at the lab.”

We had to start the extraction process.

“I brought breakfast,” I said, “for all of us.”

It was best, I thought, to do it this way. Then depart with Paul, leaving the mother with the balm of his impression on the sofa and his number on her phone.

Paul pulled himself from her sorrow and his to the mass of red and bleeding flesh I’d cultured overnight.

“This is your brain,” he said. “This is your soul. Lean near and you can feel it.”

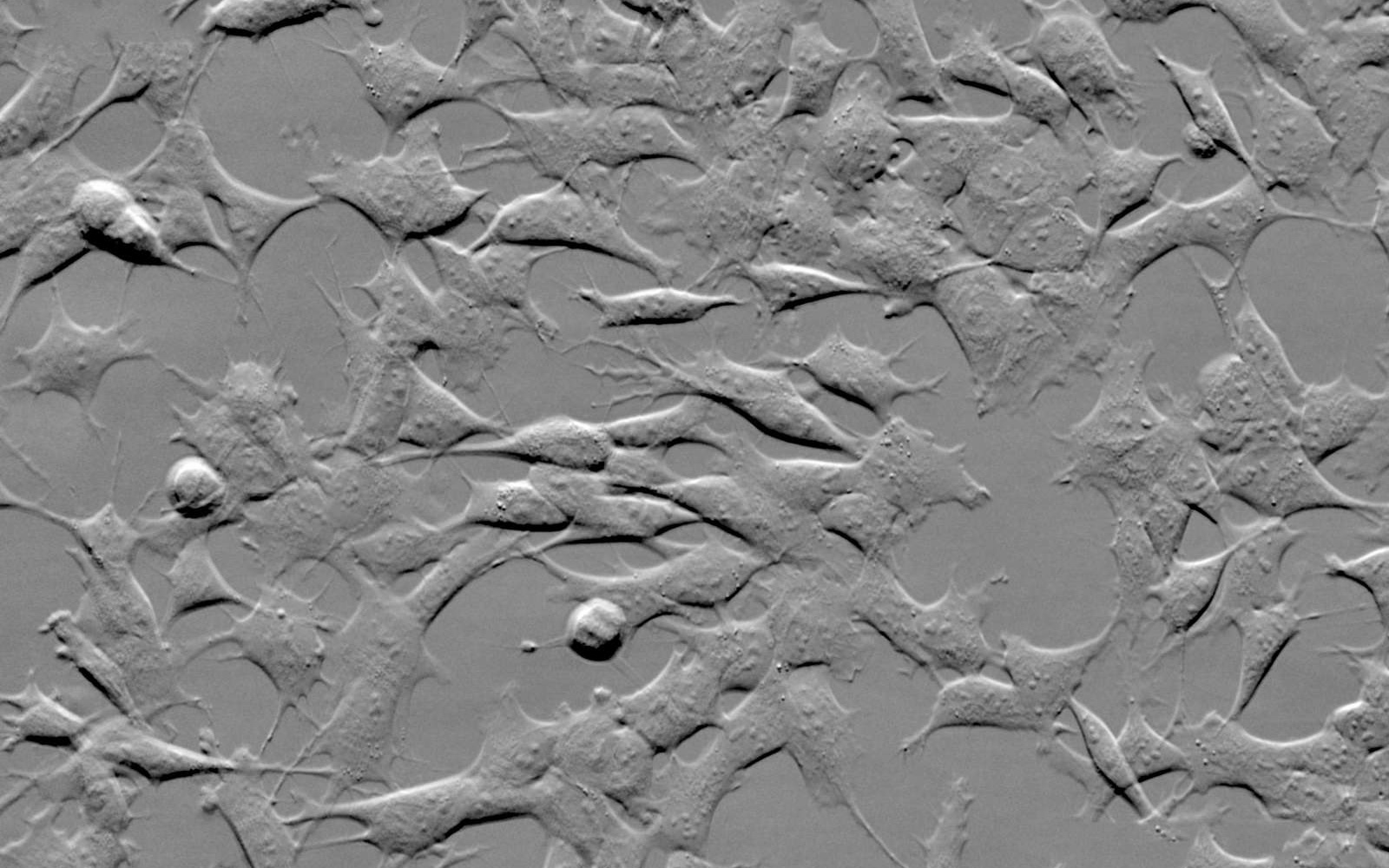

Heart cells beat spontaneously in a culture dish; it is a miracle of cellular engineering. Nerve cells, however, appear to do nothing while obscuring deep within a spiritual essence that only Paul could detect.

If the project was successful, it would be because Paul was the perfect catalyst.

But we had to be quick. In the past both of us worked together on the cardiac cell purification, but now Paul did the heart while I did the brain. Our normally long days were even longer.

The room was hot from too much equipment packed into a small space. At times I stood before the portable A/C, feeling almost light-headed from the outer swelter and inner turmoil. Raising my eyes, I saw the soup of mother tears, colorless in a clear plastic tube. Soon to be pink like the rest of the media. Pink from phenol red.

I wondered if we should add my tears, too, or Paul’s.

Sweat from hot nights lying awake in depth of anguish.

Love sweat from nights with a lover.

Music on the iPod: Everybody Hurts.

“Do you think that’s the right music?” I asked.

“They need to be sad,” said Paul, “just at the beginning, so they’re motivated to question, reach out for answers, for each other.”

We added fresh oxytocin, now supplemented with prolactin, the mothering hormone. I held the dish in my double-gloved hands and tried to imbue its contents with my own heartfelt zeal.

We placed each cell type into the appropriate chamber of the microfabricated co-culture device. Beneath the microscope the cardiac cells beat in harmony.

Years ago, just after starting in the lab, Paul had surprised me with tickets to the symphony. He sat next to me in the theater, dressed better than I would ever see him again. He said that once the music started, I should close my eyes and imagine I was listening to the universe.

“This is what we do.” His seat creaked as he adjusted his legs. “We find life’s music and use it to fill a tube.”

That night I heard music in a whole new way. Afterward I went home and lay on the sofa in a fog, bedazzled by these new cosmos sounds that were suddenly everywhere.

Now I stared at the co-culture device perched on the microscope. From the iPod came Mahler’s Symphony No. 5, said to represent his love song to his wife. Paul and I just stood there next to each other once again, exhausted and sweaty under the yellow disposable gowns.

Silly yellow clowns toying with the big everything.

“Next week we can confirm the morphological connections by immunostaining,” said Paul.

His hand trembled just a bit, strain of emotion. So many years of failure.

“Should we get some dinner?” I asked.

“Not tonight.”

“Are you sure?”

Paul was so thin, his body starved for the essence he should have used for himself but instead threw into every experiment.

“I got a kitten,” he said.

What?

“You got a kitten?”

“An orange kitten, for Maria.”

Maria the mother.

“I have to go home and get it,” he said. “Then go to her place.”

Will you stay with her?

I wanted to ask but didn’t.

“OK then, see you tomorrow.”

***

The heart-brain co-culture failed. The two cell types connected but then died. I bleached them and sucked the remains into the waste. Paul stayed outside, in the hall.

I met him there afterward.

“I just couldn’t do it,” he said.

“I know.”

“Maria’s daughter died for nothing.”

“Her other organs saved lives.”

“What do I tell Maria?”

He was still seeing her. Two people with nothing to give but a kitten.

“Tell her we did our best.”

Tell her she’s acquired your intense dark eyes staring into hers, for whatever that’s worth.

“We’ll get another chance,” I said. “Go home. I’m going home.”

***

As always it happened without notice. This time a young man killed in a car accident. His parents were already dead; he wasn’t dating. Only a sister was there at the hospital, overwhelmed at the news of this latest tragedy.

She stood at the ventilator and stared into its hideous blue-white screen.

If we had love. That’s what Paul thought. I could see it in his eyes. We could give it to this poor woman.

Instead we took her brother’s heart, the pinkish folding brain.

“But he wasn’t in love,” I said to Paul, when we were back at the lab.

“He loved someone. His sister, the memories of his parents.”

“You think that’s enough?”

“Friends, maybe.”

But we’d had so many lovers already, and all their cells had flagged and withered.

We tried again: tears, oxytocin. Paul’s own sweat from running on the treadmill, a whole week apart and aching to see Maria.

He had a photo of the orange kitten, bigger now and less kitten-like, on Maria’s lap and fast asleep. He kept it at his computer.

“What do you expect from that relationship?” I asked.

“A little less empty.”

“Is she ready?”

“Am I? I’m lost in this world. I’ve always been lost.”

True genius is always the outsider.

The cells didn’t die. The co-culture thrived and connected. We harvested the supernatants, ground up the cells. Samples accumulated in the freezer. We prepared extracts and injected them into mice.

Held our breaths.

The mice watched us with their little beady eyes. It was hard for Paul, using another living being as an unwilling test subject.

I reviewed the video footage—24-hour surveillance of the mouse cages. Paul brought Maria to the lab and they joined me. They sat near each other, huddled together like homeless children.

Then one day one mouse bit another. The bitten mouse retaliated. Another mouse joined in. We separated them, grabbing each one by its own little tail.

But the other mice, the ones still together in other cages, they did the same thing. They were hostile, angry and intolerant.

I sent Paul home and spent the whole night alone, watching over them. Maybe this was just a phase, I thought. The transition was a state of emotional turmoil, and it would pass.

But it didn’t.

Days passed. Weeks. I stood in the mouse room, in the dry stink of mouse cages, and with my eyes I scanned the array of tiny vessels each with an individual mouse. All separated for their own well-being. Even so they scratched at each other through the plastic, squeaking plaintively, angrily.

Paul and I went back to the living sister. Was her brother angry? Unhappy?

The parents were alcoholics. They died driving drunk. Even before that the children were largely abandoned; an unwelcome distraction from more important things.

How did we miss that? But we were desperate, so many years of failure.

We sat alone at a table in an all-night diner, drinking cheap coffee from brown plastic mugs. We’d met with the sister a second time. She’d left hours ago but still we remained, glued to our respective seats, unable to face the horror of what we’d done.

“Hate is stronger than love,” said Paul. “It’s the only explanation.”

“No, that’s not true.”

“No? Look at the world.”

All the years we had cells from lovers. But we couldn’t know how much they loved. Not really.

“There are too many unknowns,” I said. “It’s not the only explanation.”

Paul stood up and left. I got a refill on my coffee and left an hour later.

***

The mice kept hating.

We crossed them with normal mice; the offspring hated, too. The trait was heritable and dominant.

“We made hating cells,” said Paul. “The cells made hating mice.”

“It’s proof of concept,” I said.

“That we can mass produce hate?”

“That we have cells that create an emotion.”

“But we can’t publish.”

It couldn’t get out, said Paul. It was too dangerous. So one night we stood in the lab, a dish of cells in the containment hood. Once before, when the mice first started hating, I’d asked if we should kill the cells, wipe them out. But Paul had hesitated, reluctant to relegate years of his life and mine to obscurity.

“Should I kill them?” I asked, again.

Paul stood where he was, and this time he nodded, slowly.

Yes.

It wasn’t reported what we did. I bleached the cells, the frozen cell stocks, all the supernatants and extracts in the freezer. I killed the mice. They watched me as I collected their neighbors and it gave me a horror feeling that I was killing them because we’d made them into monsters.

For our records, we kept the methods but discarded the data.

“What do we do now?” I asked.

Paul and I sat in his office, a big wooden desk between us. He had diplomas on the wall, awards, articles regarding his humanitarian exploits all around the world.

Ten years had passed since I started in his lab, his only postdoc, his only employee; maybe his only friend until Maria.

“I’m tired,” he said. “Are you tired?”

“I am.”

“But I’m willing to try again.”

If he would, then so would I.

Provenance: Submission

Liz Fyne has degrees in biology and neuroscience and spent over 14 years doing biomedical research before she turned to writing fiction. She has two stories published in anthologies. Additional stories are published in 34thParallel, Intima: A Journal of Narrative Medicine, and Literary Orphans. She is also author on multiple scientific publications and a peer-reviewed book chapter. Learn more about her at lizfyne.com.

Liz Fyne has degrees in biology and neuroscience and spent over 14 years doing biomedical research before she turned to writing fiction. She has two stories published in anthologies. Additional stories are published in 34thParallel, Intima: A Journal of Narrative Medicine, and Literary Orphans. She is also author on multiple scientific publications and a peer-reviewed book chapter. Learn more about her at lizfyne.com.

Featured Image: “SH-SY5Y Cells . . .” by ZEISS Microscopy is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Cindy Fazzi

December 7, 2018 at 6:07 amWhat an original voice! A great example of how science can inform fiction and how fiction can make science interesting.

Liz Fyne

December 7, 2018 at 7:20 amThanks, Cindy!