The Cabin

No amount of wishing would make things real. Regardless, Clayton Jeffries still wished the snow would stop. Every day since he’d been forgotten in the cabin, since his first day in the cabin, he still wished.

In the beginning, he thought maybe the snow stopped during the night. Like home down South, it only rained while everyone slept. After several months of being cooped up in this one-room cabin surrounded with stale air and relentless snowing, Clayton started to stay awake through the night, hoping to catch a glimpse of the bare sky and see something other than white. Sometimes, he’d hope to see the Shrubs come to life while wishing for some reprieve from whatever this experience was.

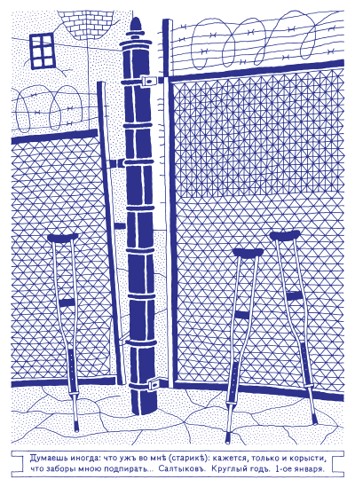

The snow fell like it always fell. Clayton sat in his chair, face pressed against the glass, and counted the Shrubs. Why were there Shrubs this far north? Clayton didn’t know. He didn’t wonder either. He’d stopped wondering about these things months ago. Now Clayton just counted the Shrubs. Eleven. Counting was less taxing than wondering. Eleven Shrubs wrapped in burlap sheets. Eleven Shrubs frozen in the ground and covered in snow since he arrived.

If even they were Shrubs.

Sometimes, instead of thinking about why the Shrubs lived this far north, Clayton peered through the snowflakes, imagining the Shrubs to be people. The twine securing the burlap around the Shrubs looking like belts. Or frozen people looking like Friars. How did he think of Friars? They must have looked like that when they knocked door-to-door collecting money for the church. Money for the poor. Always collecting. Friars wearing their tattered burlap sacks as clothing. He imagined a clan of frozen Friars forgotten like the forgotten Clayton.

Not really. No matter how lonely he felt, Clayton knew he wasn’t forgotten. They’d come for him, eventually. They wouldn’t just leave him there. The people he surrendered himself to, they were watching him. They couldn’t leave him there. He knew this as a fact like someone knowing they’re in a dream but still won’t wake up. This type of knowing didn’t give him much comfort.

Sometimes, while watching through the snowflakes, Clayton thinks the Shrubs are standing in a row. Some days, he sees them dressed in single file. Other days, when Clayton catches a glimpse of the Shrubs through the sheet of white snow, he’s certain they’re huddled in a circle. In the center of their gathering, he imagines a barrel burning to keep them warm.

The red light on the camera dome blinked from the ceiling. Blink. Blink. Blink. Always blinking; night and day. Always snowing; day and night. Never knowing where the camera was pointed, never knowing if even there was a camera inside the dome. Sometimes Clayton thought the dome was just a dome with a blinking light to make him think they were watching, just like in those quick-marts and liquor stores.

Clayton thought about what this camera might be meant to deter him from.

He didn’t dare speak to himself. If they could hear him, Clayton didn’t want to appear crazy. He wasn’t crazy, at least that’s what he assured himself. But he knew how an appearance often becomes an identity and that even the appearance of crazy might cause him to be locked away.

Six months of solitude. A single-room cabin, somewhere up north. It would be good for him to get away. Everything would be provided. They said he would be compensated for his time.

“Stocked and locked,” Clayton said while the blood immediately drained from his face.

He pretended as if he never said it. He wasn’t sure whether the camera could hear him, so he continued to stare out the window. Through the blowing snow, Clayton thought he saw the Shrubs huddled into groups of three. He must being seeing things, he assured himself. Since there were only eleven Shrubs, groups of three would mean now there were twelve.

Clayton looked away, pausing on the scene-scape calendar taped to the fridge. When he’d first come to the cabin, he’d tracked the days by crossing each square out. Now, Clayton still kept track by crossing out the days as they passed, though he wasn’t confident his count was accurate. The days dissolved into nights and nights into days. Sometimes he questioned whether he crossed days off too frequently or not frequent enough since it was impossible for him to tell how long he’d been locked in the cabin.

A gust of wind hammered the window and Clayton jumped.

Did one of the Shrubs throw something at the glass?

“No,” Clayton said out loud without realizing that he spoke. “Shrub people have no arms to throw with.”

The last uncrossed day on the calendar was an unmarked square claiming it was March 17th. He studied the month’s picture: fog on a pond in a barren canyon. No snow. He returned his attention to the date. Clayton was thankful it wasn’t Friday the 13th, even though he’d never been superstitious. Friday the 17th was just a regular day. Clayton thought about flipping forward through the calendar to find the next Friday the 13th and to determine the last Friday the 13th. He thought about these things until the thoughts passed. Then he began to question if one of the Shrubs actually threw a snowball at the window.

Without realizing it, Clayton wondered for the first time in a few months. He’d thought things and imagined. He also counted things, but he never wondered until he recognized a foreign feeling. Wonder felt the way possibility feels. Not possibility like ‘all things are possible with God’ possibility; possibility like when you’ve exhausted all other resources and suddenly discover an option you’d never thought of before that just might work.

Wonder felt like this.

The Shrubs formed a row as if they were kids in the school yard playing whatever games they played nowadays. In the space between the snowflakes, Clayton heard them chant.

“Red rover, red rover, we call Clayton over. Red rover, red rover, we call Clayton over.”

He was surprised the Shrubs knew his name. He’d never been outside. Clayton had never introduced himself. Still, the chant continued. The Shrubs were calling him over. Clayton was sure of it.

“Red rover, red rover, we call Clayton over.”

Clayton felt a warmth in his chest.

“They want me,” he said. Whether he was uncaring or unaware, Clayton repeated the words again, “They want me.”

Like a puppy hearing a command to walk Clayton wagged his head side-to-side, looking. He didn’t know what he was looking for; only that looking seemed the appropriate thing to do.

On a hook behind the cabin door, a burlap sack hung with twine cinched tight around its center. It was the same twine the Shrubs wrapped around their midlines. Why hadn’t he noticed the outfit earlier?

“It doesn’t matter,” he said. “I noticed now.”

He stood up from his seat at the window, undressed in place, then walked naked to the door. Clayton ran his hand across the sack’s material. Burlap was much softer than he had imagined. Maybe Friars wore burlap because the material felt nice against their skin, not because they were poor.

Clayton smiled his first smile in a long time.

The snow still fell, the camera still blinked, but he forgot both those details once the Shrubs called him by name.

“They called me,” Clayton said again as he pulled the burlap sack over his head and tightened the twine around his waist.

He returned to the window and looked out, hoping to see the Shrub people still standing in a line, still calling his name. He sought for space between the falling snowflakes to hear the chant.

Outside the window was white. The Shrubs couldn’t be seen and the chant was silenced by the wall of snow.

Of course the chant couldn’t be heard, Clayton rationalized. Who could hear anything in that chaos?

“Yes, who indeed?” he asked.

To Clayton, the snow was noise, the static of an old television hushing and shooshing and creeshing all at once, and thought the snow outside looked like an old television set with nothing but static displayed on the screen, only whiter.

Clayton thought about how long it took him to dress and how long he’d been staring at the white outside and then instead of thinking further, he walked to the calendar and crossed out another day.

It was now Saturday, March 18th.

In the corner of that calendar day’s square was a hollow circle, indicating a full moon.

Doesn’t matter, Clayton thought. Can’t see the moon anyhow.

He had forgotten the camera watching him, as he sometimes did, until its blinking light caught the corner of his eye. He cocked his head toward the ceiling and smiled. How silly he must look wearing a burlap sack. He wondered if the person or people on the other side thought he looked like a Friar he thought the Shrubs had, and if they too had pictured him as a Friar going door-to-door like the Jehovah’s Witnesses did in his home town, peddling whatever it was Jehovah’s peddled on their trips door-to-door. Did the watchers think the burlap was rough and uncomfortable? Would they ever have the opportunity to wear it? To discover how soft it actually felt against the skin?

This intense moment of wonder didn’t feel like that sense of ‘possibility’ he felt earlier. This time, as Clayton wondered, he felt wonder like how when you see someone doing something you never thought to do, how as you watched you decided to try, and by trying, discovered that there was indeed pleasure where you were convinced no pleasure could have existed. Clayton thought about the first time he tried sushi. That kind of wonder.

Another smile crossed his face and went back to the window. The snow, which had stopped blowing, was falling as it had when the Shrubs first called him to join their game. He squinted, trying to focus his eyes through the snow and counted eleven shadows. Clayton tilted his head and listened.

“C-L-A-Y-T-O-N…” called one of the smaller Shrubs.

He furrowed his brow and looked harder out the window. Clayton opened his mouth, listening closer. The Shrubs were standing around their barrel, fire burning. He knew this was his chance.

Clayton started toward the cabin door and, for the first time since he decided to join the Shrubs, he questioned if the door would be unlocked. If it was locked, how would he open it? He didn’t want to let this thought turn into a worry, so he tried the handle. It turned.

Had ever even been locked? The wonder like how some people fret over how things could have been if only they’d known sooner or if they’d not found out as soon as they had. Clayton dismissed this feeling of wonder immediately since he did not enjoy it.

A cold gust of wind greeted Clayton as he opened the door. Through the falling snow, he could see a faint flame burning in the middle of the distant shadows.

He took a deep breath and let his air expire. He glanced at the calendar one last time, grinned, and stepped into the night to join the friends calling him.

Author Biography

Andrew Lafleche is the author of No Diplomacy; Shameless; Ashes; A Pardonable Offence; One Hundred Little Victories; On Writing: and Merica, Merica on the Wall. He is editor of Gravitas Poetry, and the Evil Musings anthology. Lafleche served as an infantry soldier from 2007-2014. He earned an MA in Creative and Critical Writing from the University of Gloucestershire.

Visual Artist Biography

Dmitry Borshch was born in Dnepropetrovsk, studied in Moscow, today lives in New York. His drawings and sculptures have been exhibited at the National Arts Club (New York), Brecht Forum (New York), ISE Cultural Foundation (New York), the State Russian Museum (Saint Petersburg).

No Comments