Ekphrasis

Zak Salih

1.

The Shaft Scene

17,000 B.C.E., mineral pigment on stone

Sebastian Mote is ten years old. He’s in his father’s basement with Ozzy Plott, a friend from school. Sebastian sits in an old wingback chair, flipping through an enormous book on the history of Western art, trying to stay busy while waiting for his turn on Ozzy’s Game Boy. He tosses the thick pages, working his way to the end of the book then back to the beginning. He thinks the more he concentrates, the more he absorbs his mind in what’s directly in front of him, the faster time will pass until their agreed-upon, ten-minute rotation. Sebastian comes across reproductions of primitive paintings on the rock walls of some old French cave. He stares at the galloping herds, traces the curve of a cow’s brown back with his finger. He turns a page, sees a crude illustration of a bull knocking over what looks like a man. (It reminds Sebastian of drawings on the school blacktop: the flowers and suns and salamanders in colored chalk, the cuss words and boobs and boners in black spray paint.) There’s a slash above the man’s stick-figure legs that looks like a dick. Below the image is a caption: Photograph of Walls in the Shaft of the Dead Man at Lascaux Cave. Sebastian looks up at the back of Ozzy’s head, the neck poking from his sweater, the fine hairs like kiwi fuzz. Sebastian asks: Is it my turn yet? Ozzy says: No. I haven’t died yet. Possessed by an uncanny, inexplicable compulsion (the same one, he imagines, that must have propelled these ancient cave people to decorate their ancient cave walls), Sebastian longs to reach over and place his hand on Ozzy’s neck, to touch each individual hair, to feel that secret warmth. He wants to fall into Ozzy’s lap and curl up, kitten-like, in those long arms. I’m going to take a piss, Sebastian says. He rises from his father’s chair and pretends to trip on the hassock. He drops the art book on the carpet and throws himself, awkwardly, onto Ozzy’s back. Shit, Sebby, my game. Sebastian knows he can’t stay here for long. Pushing up against Ozzy’s shoulder blades, he brushes his lips against the back of Ozzy’s neck, feels the tickle of near-invisible hair. Ozzy stiffens, then shoves Sebastian off. Stop that, he says. Then: Weirdo. Ozzy reaches for his Game Boy and resumes playing. The two boys spend the rest of the afternoon in silence, Ozzy on his Game Boy, Sebastian back in the chair with the art book in his lap, thinking of empty caves and echoing wind, of holding someone close by primal firelight.

2.

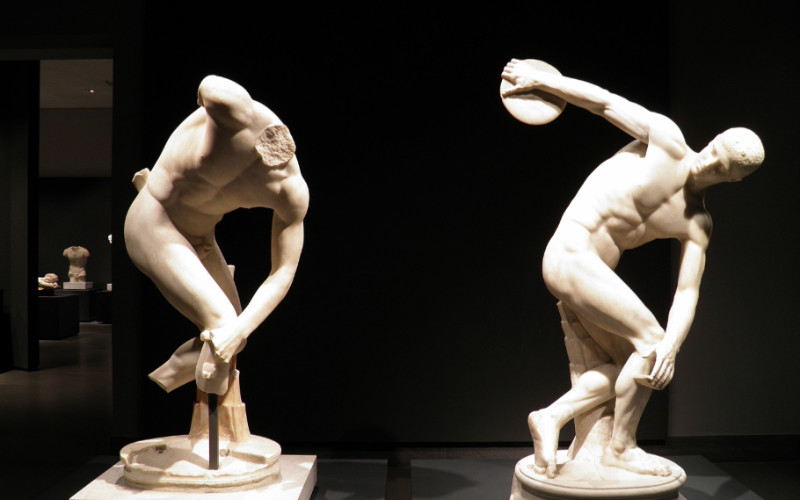

Statue of a Bearded Hercules

68-98 C.E., marble

The first buttock Sebastian feels, other than his own, is made of stone. He’s six years old, following his mother and father through the cavernous belly of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The enormity of the space, the way it carries voices, makes him uneasy. The family wanders among Greek and Roman statues and sarcophagi. Sebastian thinks: All of these statues are broken. Why doesn’t someone fix them? Still, he’s captivated by all the pale, cold flesh on display: the smooth muscles and powerful poses, the stubby penises with their testicles like tiny plums. His mother draws his attention to a tall, imposing man whose head is being swallowed by a lion. That’s Hercules, she says. He was an ancient hero. He killed that lion and is wearing its skin. See the paws. Sebastian stands and looks with his mother. Then she moves on to follow his father toward a giant stone column (also broken). Sebastian walks around the statue of the ancient hero, embarrassed and entranced by marble buttocks as big as his head. He sees a huge dimple in the left one, as if someone had punched it. Without another thought, Sebastian steps onto the small dais where the man of marble stands and, stretching on his toes, places a hand inside the concavity. He feels a shock of cold, then a growing warmth. (Whether it’s his hand or the statue that’s warming, he can’t decide.) The museum guard barks. Sebastian’s father hisses as if he’s touched hot flame. His mother rushes over and pulls him away from the statue. No touching, she whispers. Later that night, back in their hotel, his mother and father already lost to sleep, Sebastian thinks about the marble statue of Hercules in the dark and quiet of the museum, stuck in his eternal stance, grateful for a brief moment of contact with a human hand not wielding a chisel.

3.

Portrait of a Man (Self Portrait?)

Jan Van Eyck, 1433, oil on canvas

His sophomore year at Jefferson University, yawning through an early-morning survey of European painting, Sebastian thinks about what he’ll wear when he meets up later that evening with Calvin. They’re going to see a student play directed by Calvin’s friend. Calvin is the first out gay guy Sebastian has ever known, has ever agreed to spend time with outside of class. He’s intimidated by the way this journalism student from New Jersey, adopted from South Korea at age five, moves through campus. Calm. Confident. Assured of himself and his identity in a way that seems impossible to Sebastian who, at twenty, remains unsure of his station in the world. While Sebastian’s not out to his parents yet, he’s made out with several closeted guys, even masturbated with one of them in the gym shower just last month (an act that repulsed him for its animal baseness, the grunt and release, the quiet return to different planes of existence). But this. This is a date. An activity. Possibly a meal after. Possibly a late-night walk along the train tracks that cut through the southern corner of the university. And possibly. At the front of the sloped lecture hall, the professor pulls up a portrait Sebastian has seen countless times in his other art history classes: the stern face, the wrinkles along the eyes, the cleft of cheekbone suggesting the skull hidden underneath richly painted flesh. That evening, after hamburgers, Sebastian and Calvin walk not to the train tracks but back to Calvin’s off-campus apartment, where Sebastian is penetrated for the first time. Calvin is barely inside before Sebastian asks him to stop. The dull pain, the sense of claustrophobia in his own body, is too much to bear. Calvin sighs and flops backward on the bed, rolls up the lube-slick condom and tosses it across the room. Sebastian waits in terror for the smell of shit. To compensate for his poor performance, he crawls over and begins to bob his mouth up and down on Calvin’s erection. He adjusts himself on his forearms and, as he does, notices Calvin’s flannel bedsheets, a red as deep as the chaperon he saw that morning piled on Jan van Eyck’s head. Afterward, there’s no mistaking the silence, the lingering smoke of disappointment. Mouth still salty, Sebastian stares at the poster for 2001: A Space Odyssey tacked above Calvin’s desk. He reads the tag line over and over: An epic drama of adventure and exploration. I really just wanted to be inside you, Calvin says. Then: Maybe you should try exploring that part of yourself a little more? Maybe you’re right, Sebastian says. He looks away from the poster to his fingers tapping against the red flannel bedsheet. He thinks, Als Ich Can.

4.

Saint Anthony Tormented by Demons

Martin Schongauer, 1470s, engraving

On an August weekend before the start of his junior year at Mortimer Secondary, his parents in Indiana for a college reunion, Sebastian sees his asshole for the first time. He goes to the garage, gets a screwdriver, and takes down the narrow body-length mirror from behind his bedroom door. He places it on the floor, kicks off his shorts, and shimmies his hips so his boxers slide to his ankles. Sebastian steps out of his underwear and stands over the mirror, a naked colossus over a reflective, one-dimensional Rhodes. He looks down past the small swell of his belly, the stocky legs dusted with hair, the modest droop of his penis, his testicles in mid-retreat, as if ashamed by this experiment. Sebastian squats down and looks at the tiny hole. He never realized how much hair there was. That’s a hairy asshole, he thinks with hilarious clarity. Taking the index finger of his free hand, the other bracing himself against the dresser, Sebastian gingerly pokes the orifice. First contact. He doesn’t dare slip a finger inside. The thought frightens him, means crossing a threshold from which he can never step back. Sebastian stares at his asshole for several minutes, flexing his abdominal muscles, trying to make the pucker speak. It’s a moment he thinks of again, five years later, in the stacks of the Jefferson University library. He’s working on his senior-year thesis when he comes across a horrifying 15th-century engraving of a bored Christian saint assaulted by demonic hordes. He finds himself drawn to one demon in the lower right-hand corner of the work, clutching the saint’s left knee, lion-faced, batwings rimmed with suckers. He focuses on this devil’s own asshole, swollen and puckered as if preparing for a kiss. Sebastian instinctively clenches his own buttocks, as if to remind himself that he’s seen his own asshole before and no, it’s nothing like that.

5.

Portrait of Henry VIII

Hans Holbein the Younger, 1536-1537, oil on canvas

Once again, Sebastian eats dinner at Ozzy’s house next door. Once again, the family eats dinner with the television on. Ozzy’s father, full-figured, lordly, sits at the head of the glass table through which Sebastian can see pairs of crossed legs. Pass those potatoes, Ozzy’s father says in his tyrannical voice. The roast bleeds on its platter. Ozzy swings his feet and eats in silence. The two boys can’t stop talking when they’re upstairs alone in Ozzy’s bedroom. Downstairs, at dinner, they’re always silent. Sebastian hates these meals. He wishes he and Ozzy could take their plates and eat upstairs, alone. With every bite of red meat, every sip of soda, Sebastian looks up at Ozzy’s father, watches the powerful jaw muscles masticate under a heavy beard, watches the kitchen light bounce off the man’s forehead. Just like a baby, Sebastian thinks every time he sees it. On the evening news, a reporter interviews a man about palliative care for AIDS patients. Faggots, Ozzy’s father says. He shakes his head. It will be another five years before Sebastian begins to associate that word with himself, or rather with someone inside himself, living in his skin and operating his brain and body. Ozzy’s mother looks up from her dinner. Henry, she says. Please.

6.

The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian

Guido Reni, c. 1615, oil on canvas

Sebastian spends his two years of middle school returning again and again to the painting of a young man tied to a tree. He ignores the two arrows—one in the ribs, one in the armpit—and focuses on the pale nipples, the hairless arms, the upturned face, the giant eyes, the curly hair. He dwells on the lower quarter of the image, the smock loosely tied to narrow hips, revealing a shadowy opening into which Sebastian wants to slip his hand. He wonders what that would feel like. One evening, after dinner, Sebastian tries to draw the boy on a sheet of graph paper while the thick art catalogue shields his erection. His mother walks into the living room. Huh, she says, you really like that picture. Sebastian is paralyzed. You know, his mother says, that’s your namesake right there. I saw that painting long before you were born. In Spain. Sebastian’s mother leans over, rests her chin on his shoulder, looks at the painting with him. That face, she says, it’s just unbelievable, isn’t it? I could never forget it. It was my idea to name you Sebastian, as soon as I found out you were going to be a boy. She makes playful jabs with her fingers at his torso. He tries not to squirm. Please God, he thinks, don’t let this book fall off my lap.

7.

Watson and the Shark

John Singleton Copley, 1788, oil on canvas

Sebastian is on a field trip with his third-grade class to the National Gallery of Art. His mother is a chaperone, keeping up the rear behind a group of eight kids who follow the docent through the galleries. At one point, they find themselves in front of an enormous oil painting. That doesn’t look like a shark, one student says. That’s because it was invented by Mr. Copley, the docent explains. They weren’t really sure at the time what sharks looked like. A student asks: Why is that man naked? I think it’s a girl, another student says, look at her long blonde hair. A new student, Oscar Plott, asks: Did he die? No, the docent says, the young man was rescued. He lived a long, happy life. Though he did lose part of his leg. Eww, someone says. Later, during lunch, Sebastian sits next to Oscar (I go by Ozzy.) in the grass outside the museum. The new boy just has carrots with his ham sandwich, so Sebastian shares his grape Fruit-Rollups. The two boys spend the rest of lunch pressing small squares of dried fruit into the roofs of their mouths. They attach small strips to their tongues and pretend they’re lizard people.

8.

Saturn Devouring His Son

Francisco de Goya, 1819-1823, oil on wall

Sebastian shouldn’t be looking at porn on the Internet. He doesn’t know what time his father will get home from his afternoon lectures. With every new picture he loads, Sebastian thinks this will be the one he comes to. Then he can clear the browser history and close the computer cabinet door. While he waits for an image to load, he clicks on more hyperlinks, opens up new browser windows. Soccer_boner.jpg. Johan_Orgy_003.jpg. Gay_blowjob_HOT.jpg. An image of two teenage boys fellating one another on a white bedspread finally loads. This is it, Sebastian thinks. He’s pleasuring himself, imagining what it would be like to take someone else’s penis into his mouth, to roll it around with his tongue, to avoid scraping it with his teeth. Then the door to the garage opens. Sebastian shuts off the computer monitor and freezes. Mouth agape, eyes wide. Thank God I only unzipped my fly, he thinks. Thank God there’s a solid back to this kitchen chair. His father says: How was school? Sebastian just continues to stare. There’s a moment of silence, then his father says, Oh, and walks back outside. In the blackness of the computer monitor, Sebastian sees the garage door close, sees his own shocked and distended visage. It’s a crazy face he’ll encounter again in college while studying the late paintings of a mad Spanish artist. The face of someone caught in wild abandon. The face of someone putting things in his mouth he shouldn’t.

9.

The Origin of the World

Gustave Courbet, 1866, oil on canvas

Sebastian, at sixteen, is desperate not to be what he has the sinking feeling he might be. For one whole week in February, after school and before homework, he goes up to his room, unfolds a printed copy of a painted vagina he keeps behind his dresser, and masturbates while forcing himself to think of pussy, of juicy cunts, of throbbing clits. Two times he’s successful: Monday and Thursday. Every other day, he gives up after five minutes, tucking his raw penis back into his pants and taping the folded printout back behind his dresser.

10.

The Swimming Hole

Thomas Eakins, 1884-1885, oil on canvas

Here, his father says, and hands Sebastian a paperback copy of The Complete Poems by Walt Whitman. He takes the Xeroxed pages from his son’s hands. You might find other poems you like in there, too. Sebastian’s twelfth-grade English class is reading Song of Myself. It’s beautiful, Sebastian thinks when his teacher reads passages in class. He thinks, repeatedly, about the lines, An unseen hand also pass’d over their bodies, / It descended tremblingly from their temples and ribs. It’s a little gay, the boy in the next row says. Let’s not use that word, his teacher says (unaware, or perhaps not, that many students use this word to describe him outside of class). But yes, Walt Whitman was a homosexual. A fact all the more obvious by the front cover of the Penguin Classics edition Sebastian’s father gives him. Sebastian wonders: Is this a trick? Does his father want to see how he reacts to these two boys on their slab of rock, one in dramatic contrapposto, the other sitting up on his side, hand raised, head turned, as if unable to look directly at the swollen buttocks just within reach? Sebastian holds onto the paperback long after his class’s poetry unit ends, puts it on his bookshelf next to the children’s encyclopedia he hasn’t opened in years. In his room, at night, Sebastian takes the book down. He foregoes the poetry in favor of the front cover. The limber, perfectly proportioned body he wants to slide along like river water. A butt between whose cheeks he wants to nest for days. A body that begs to be held, to be oh-so-gently manipulated. The pinnacle of young male beauty. Sebastian is transfixed. Periodically, he lies face-down on his bed, chin hanging over the edge, the book lying on the floor a foot below him. Sebastian grinds himself into the mattress as if it were that same soft body. After he orgasms, Sebastian lingers. He imagines it’s not the tired twin mattress he’s dozing against, its sheets crowded with the thunderheads of old come stains, its springs exhausted from years of constant frottage. Instead, it’s the standing boy’s sun-warmed body. While others cavort in the stream, Sebastian and the boy are alone with one another. This, Sebastian tells a lover a decade later as they lay in post-coital exhaustion, was when I first fell in love with another guy. Wait, Sebastian says, I take that back. There was someone before that.

11.

Number 1, 1950 (Lavender Mist)

Jackson Pollock, 1950, oil, enamel, and aluminum on canvas

That’s in the middle of the country, right? It’s late spring in 1994. Sebastian and Ozzy are out on the driveway of Sebastian’s house, pitching racquetballs against the closed garage door. Yeah, Ozzy says. And your dad’s got a new job there? Yeah, Ozzy says. They throw the blue balls for another few minutes. Wow, Sebastian says, Ohio. It sounds, to him, like the name of another galaxy. Sebastian throws his racquetball harder, wants to see if he can punch a hole through the painted wood. Then he says, I’m going to miss you. We’ll be here for another month or so, Ozzy says. And you can come visit us. My mom already said you’re invited. Another minute of silence. Then, because Sebastian fears he’ll have no other opportunity, he leans in and whispers, Hey, remember what we did that one time a few months ago? What one time? That one sleepover. The one with Aaron and Ryan? No, the one with just us, when we, you know. Sebastian remembers the moment vividly but doesn’t have the right words to express what they did or the deadly concern he feels about it, so he takes his two index fingers and swats them back and forth against one another. Remember? Ozzy looks away. Yeah, he says, I remember. So? I mean, Sebastian says, do you think we might. Maybe we. You can’t get AIDS from doing that, can you? No, Ozzy says. He turns to chase his errant racquetball as it rolls across the street. He comes back, throws the ball to Sebastian. Anyway, he says, I should go home. I should call Ryan and Aaron and tell them the news. Sebastian panics, then realizes what Ozzy means. He looks at his friend, who’s beaming at the prospect of moving, at the promise of a new adventure. It makes Sebastian angry, this happiness. It makes him feel like the last three years of their friendship was just a casual diversion, a dress rehearsal. He watches Ozzy dash across their neighboring yards. Sebastian knows he’s just experienced an irrevocable moment. Life could have been one way, but now it will only be this way. Sebastian stays outside and continues to throw his racquetball against the garage door, harder and harder. An upstairs window opens and his father shouts through the screen for Sebastian to stop. Suddenly, Sebastian turns away from the garage door, letting the racquetballs bounce away down the street, and throws up on the driveway in a splatter of green and gray. He feels his mouth yield to the movements of his stomach, shudders with the realization that vomiting always brings: that your body, not you, is in control. If your body wants you to throw up, you’ll throw up. If your body wants you to rub dicks with your best friend in the early-morning hours of a sleepover, you’ll rub dicks with your best friend. Sebastian feels at the mercy of something he can’t reign in, let alone understand. He steps back from the mess on the concrete, the sloppy sick sight of it, the strands of vomit mingling with tendrils from old motor oil leaks and blades of mown grass and flecks of compacted minerals. Hey, his father calls from upstairs (his voice now softer). Are you alright? I’m fine, Sebastian says. You sure? Mm-hmm. Stomach acid burns the back of Sebastian’s throat, the roof of his mouth. Okay, his father says. Maybe you should come inside now. Before you do, though, take the hose and spray that mess out into the street, will you?

END

Provenance: Submission

Zak Salih lives in Washington, D.C. His writing has appeared in publications including The Millions and the Los Angeles Review of Books.

Image by Carole Raddato via flickr under Creative Commons license

No Comments